China’s diplo-terrorism in Myanmar

Beijing associates with the lowest-level forms of terrorist and gangland violence in order to attain diplomatic objectives

In a bid to expand its diplomatic influence in Myanmar, China is supplying funds and sophisticated weaponary to a Myanmar-designated terrorist organization called the Arakan Army (AA), according to six regional experts interviewed for this article.

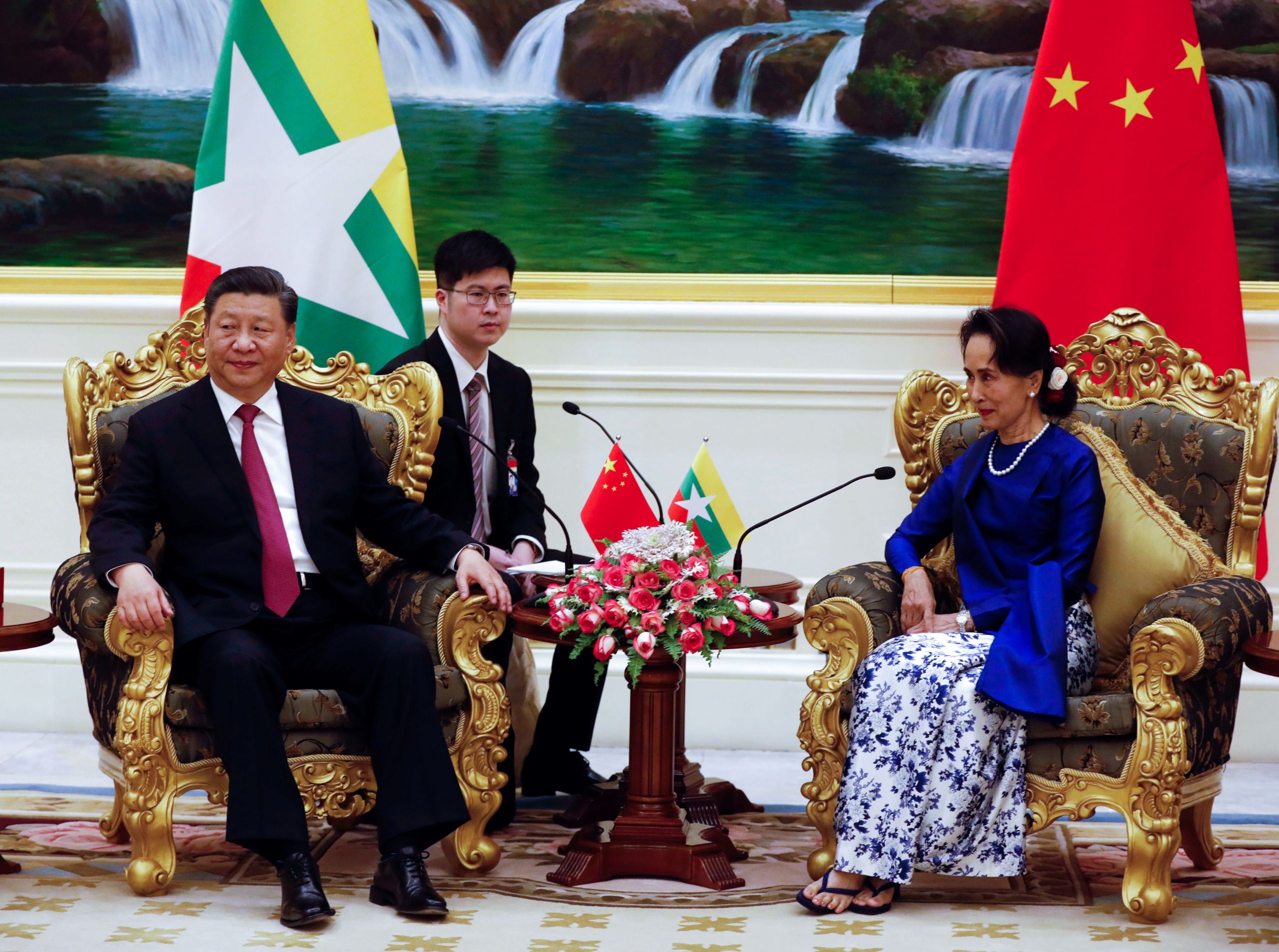

In January, China’s leader Xi Jinping was quoted by a Myanmar military source as denying that it supported ethnic militias in the Southeast Asian nation. “We categorically deny allegations of supplying arms to ethnic armed organizations in Myanmar, but they can acquire these arms by other means, so that we will look into this issue thoroughly to resolve it,” Xi said.

The next month, Chinese arms reportedly arrived on the beaches of Bangladesh, and were smuggled into Myanmar in small batches for the Arakan Army insurgent group in Rakhine State.

According to an Eastern Link article by Subir Bhaumik, the most recently-uncovered arms delivery from China was a

“consignment containing 500 assault rifles, 30 universal machine guns, 70,000 rounds of ammunition and a huge stock of grenades ... brought in by sea and offloaded at the Monakhali beach not far from the coastal junction of Myanmar and Bangladesh in the third week of February.”

A Rakhine source close to the Arakan Army claimed that the shipment included FN-6 Chinese MANPADS (Man Portable Air Defense Systems), according to the article.

A military source with experience in Southeast Asia confirmed to this author that China is providing approximately 95 percent of the Arakan Army’s funding. He said the Arakan Army has approximately 50 of the MANPADS surface-to-air missiles. The source asked to remain anonymous as he did not have permission to release this information.

A diplomat in the region communicated to the author that “seven different groups (including AA) in Myanmar received Chinese arms and support.” He said that the “Chinese object has always been to keep the West away from Myanmar by keeping Myanmar [a] weak and closed state with a poor humanitarian record.” The diplomat requested anonymity due to fear of retaliation.

A think tank analyst who also asked to remain anonymous, because he was not cleared to release the information, said that:

“The Arakan Army (AA) is being supported by China as a matter of policy in line with its support to the other [ethnic militia] groups e.g. UWSA, KIA etc. The nature of support to the AA comprises finances, uniforms, weapons, ammunition and other war like stores including shoulder fired SAMs (FN - 6). The supply of weapons and ammunition continues till this day and so does the supply of money. AA has apparently also received money to ensure they do not stray towards [China’s Kyaukphyu] Deep Sea Port.”

The Kyaukphyu Port is part of China’s Belt & Road development project and this development seeks to compete with an Indian port project just 100 km to the north.

The powerful United Wa State Army (UWSA), also an ethnic group, reportedly receives arms from China, which it then distributes to other groups. The Wa State based UWSA is allied with the Kachin Independence Army (KIA), which according to a military source, China used to create the AA.

The Arakan Army was created and trained by the KIA in northern Myanmar near the border with China. The Arakanese are an ethnic group distinct from the ruling Bamar ethnic group of Myanmar, even though both groups adhere to Buddhism. There is a history of Bamar oppression, rape, and killing of the Arakanese that drives the resistance to the capital, Naypyitaw.

According to Bhaumik, a former BBC reporter in Myanmar, anti-Tatmadaw sentiment in Rakhine State has been galvanized and quickly expanded through the influx of Chinese money and arms.

Myanmar expert Bertil Lintner agrees. “While the KIA has not benefited significantly from Chinese weaponry funneled through the UWSA, other FPNCC (Federal Political Negotiation Consultative Committee) members — the Myanmar National Democratic Alliance Army in Kokang, the Ta’ang National Liberation Army in northern Shan State, the Shan State Army-North, and the Arakan Army in Rakhine State — all have.”

The Arakan Army and diplo-terrorism

The government of Myanmar designated the Arakan Army a terrorist organization on March 23, saying that it “caused serious losses of public security, lives and property, important infrastructures of the public and private sector, state-owned buildings, vehicles, equipment and materials.”

In 2019, the group allegedly attacked four police stations, causing 20 casualties among police. Some of the police died from their wounds.

China’s Foreign Ministry spokesman, Lu Kang, did not denounce the Arakan Army when asked about the January attacks. “China supports all parties in Myanmar to promote reconciliation and peace talks, and strongly opposes any form of violent attacks,” he said blandly.

Leaders of the Arakan Army gather with other leaders and representatives of various Myanmar ethnic rebel groups at the opening of a four-day conference in Mai Ja Yang, a town controlled by the Kachin Independence Army (KIA) in northern Kachin State on July 26, 2016. (AFP photo)

Leaders of the Arakan Army gather with other leaders and representatives of various Myanmar ethnic rebel groups at the opening of a four-day conference in Mai Ja Yang, a town controlled by the Kachin Independence Army (KIA) in northern Kachin State on July 26, 2016. (AFP photo)

But China was at the same time selling arms to both the Myanmar military, and the country’s ethnic militias, including the Arakan Army, according to sources. According to a military source, “The Arakanis don’t let the [Indian] road go through the spots that they control,” because the Chinese want to block it.

The Arakan Army, which seeks de facto independence from Myanmar as enjoyed by the UWSA, has kidnapped workers on the Indian port and road project. These armed Buddhists operate in Rakhine and Chin States, and should not be confused with military attacks on Rohingya Muslim communities in the region. A small armed Rohingya group called the Arakan Rohingya Salvation Army (ARSA) also operates in Rakhine State.

Multiple sources noted that the Arakan Army is also involved in the drug trade for revenue.

“The drugs are sold on the black market through criminal organizations and local drug lords,” said an Indian expert who asked to remain anonymous as he was not authorized to speak on the matter.

A military source said the Arakan Army is engaging in opium and methamphetamine production. “This is part of the golden triangle — a lot of opium cultivation,” the source said.

An Australian academic, who asked not to be identified in order to maintain his contacts, said that there are three methamphetamine factories in Rakhine State, one of which has Chinese backers. “China’s interest is to create a pro-China faction within the Arakan Army, and to support that one in order to weaken other parts,” he said.

A view of the inside of a clandestine methamphetamine lab. (shutterstock.com photo)

A view of the inside of a clandestine methamphetamine lab. (shutterstock.com photo)

Arms smuggling, terrorism and illicit drug production endanger local communities, while the Chinese government profits from both sides. “The Arakan Army is bartering their narcotics, opium and methamphetamines with the Chinese in exchange for weapons,” one of the military sources said.

“The Chinese who are doing this business could be intelligence or private companies operating there,” he said. “When they are operating in sensitive areas they represent themselves as businessmen or contractors, but they are actually government and report to the Chinese Communist Party (CCP). The Arakan Army is definitely obstructing the [Indian] road at the direction of the Chinese.”

According to this source, China has supplied the Arakan Army with anti-aircraft guns, automatic rifles, mortars, and a Chinese version of the Carl-Gustaf 90mm recoilless rifle, which is a multifunctional weapon with an anti-tank capability. “They have everything except artillery,” he said.

China cannot claim ignorance of the Arakan Army’s terrorist activities. According to China’s own state media in March:

“The Myanmar Central Committee for Counter-Terrorism announced that the Arakan Army organized the civilians in the north of Rakhine through intimidation and attacked the army, police force and outposts under the cover of local people. In addition, they detained, abused and killed villagers, and also shot and laid mines in the village. The Arakan Army also carried out terrorist attacks on registered ships, aircraft and other motor vehicles, so it was designated a terrorist organization.... Since 2019, the Arakan Army has repeatedly committed kidnappings.”

The Arakan Army does have local support, according to Bhaumik. This may in part be attributed to a history of Tatmadaw brutality and lack of real democracy. “The popular support has significantly influenced China’s attitude towards the AA,” writes Yun Sun at the Stimson Center in Washington, DC. “As the creator and promoter of ‘people’s war’, the Communist Party of China is deeply sensitive to the power and importance of popular support.”

Tatmadaw war crimes

To subdue the Arakan Army, Myanmar’s military, known as the Tatmadaw, is reportedly using harsh tactics against civilians, aid workers, journalists, and entire villages, including air power, artillery shelling, burning huts, destroying food reserves and denying medical services and internet access. Curfews have been instituted in some villages from 9pm to 5am. A World Health Organization worker was shot and killed on April 20. Dozens of civilians have been killed, hundreds injured, and hundreds of huts burned in March alone, according to Arakan American Community (AAC) President Oo Thein Maung. He alleges that the Tatmadaw is motivated by racism against minority nationalities in Myanmar.

Military targeting of civilian populations by the Tatmadaw may entail crimes against humanity. “The Myanmar military has caused serious losses of public security, lives, and property, important infrastructures of the public and private sector, buildings, vehicles, equipment and materials,” alleges Oo Thein Maung. “Therefore the Myanmar military is, by definition, a state terrorist organization.”

If so, China is again complicit in support to state-sponsored terrorism. Since 2013, Myanmar’s military has imported $720 million in weaponry from China, including 17 JF-17 aircraft, two Type-43 Frigates, 12 Chinese Rainbow UAVs, and 76 Type-92 armored vehicles.

Tatmadaw attacks have made as many as 140,000 civilians homeless in Rakhine State, according to Oo Thein Maung. Over 100 war refugee camps “are facing overwhelming shortages of food, shelter, and medicine,” he writes. Humanitarian aid is blocked by the military to the camps, and over 10,000 acres of rice paddy were damaged in 2019 alone. “With more systematic and strategic oppression, people in the State of Arakan [Rakhine] are to face starvation, especially as the monsoon season of late May-October arrives.”

These numbers do not reflect the greater magnitude of Tatmadaw attacks on Myanmar’s Rohingya Muslims. According to a 2018 study, there were an estimated 1.1 million Rohingya who fled across the border to Bangladesh by that same year. “Rohingya people have faced recurring military crackdowns and fled from Myanmar in significant numbers in 1978, 1992, 2012, 2015[,] 2016 and 2017,” according to the study. “In August 2017 the Myanmar army burned approximately 300 Rohingya villages ... 25,000 Rohingya were murdered, 28,000 raped, 43,000 received gunshot wounds, and 116,000 beaten,” they write.

Rohingya refugees queue for a food supplies distribution at a refugee camp, Cox Bazaar, Bangladesh, Oct. 31, 2017. (shutterstock.com photo)

Rohingya refugees queue for a food supplies distribution at a refugee camp, Cox Bazaar, Bangladesh, Oct. 31, 2017. (shutterstock.com photo)

In January, the International Court of Justice (ICJ) at the Hague ordered Myanmar to take immediate preventative measures to stop genocide against the Rohingya.

According to information attributed to Gaganjit Singh, former deputy director-general of India's Defense Intelligence Agency, and one other source, China has built the most recent of three internally-displaced persons (IDP) camps in Rakhine State, capable of housing approximately 25,000 Rohingya and Rakhine families each. The IDP camps are presented as a form of humanitarian assistance but include electrified barbed wire and are more of a concentration camp than an IDP camp.

Illustrating the geopolitical complexity of the conflict, China is in competition with Israelis, according to information attributed to Singh, to supply artificial intelligence (AI) technology for the camps.

The Tatmadaw has at its disposal helicopter gunships from Russia and truck-mounted multiple rocket launchers from North Korea. Between 2014 and 2018, Myanmar got 61 percent of its arms imports from China, 20 percent from Russia, and 6.5 percent from Belarus.

Hla Phoe Khaung transit camp for returning Rohingya refugees is pictured from a Myanmar military helicopter on Sept. 20, 2018. (Photo by Ye Aung Thu/AFP)

Hla Phoe Khaung transit camp for returning Rohingya refugees is pictured from a Myanmar military helicopter on Sept. 20, 2018. (Photo by Ye Aung Thu/AFP)

China’s arms sales to the Arakan Army

Chinese arms shipments to the Arakan Army were first reported on April 22 by Bhaumik in Eastern Link, a publication focused on the connections between east India, Bangladesh, and Myanmar. Myanmar borders both India to the northwest and China to the northeast. The part of India closest to the territory of the Arakan Army is the Seven Sisters, composed of the seven states of Assam, Arunachal Pradesh, Meghalaya, Mizoram, Manipur, Tripura, and Nagaland, plus the new state of Sikkim on the border with China.

Frequent unarmed clashes occur between the militaries of China and India in Sikkim, Arunachal Pradesh, and in Bhutan’s Doklam region. The last pushing match, which included stone throwing and a fistfight, occurred on May 9 between 150 Indian and Chinese soldiers.

Impressed by the calm yet assertive demeanour of the Indian soldier. Whereas the mannerism of the Chinese soldier speaks more about their professional ethics.pic.twitter.com/cWYVqzVAIO

— Naveed Trumboo IRS (@NaveedIRS) May 15, 2020

In 1962, a dispute over Arunachal Pradesh turned into a one-month war. Ever since, China has supported rebels in India’s northeast.

Rebels from the northeast use a corridor through Myanmar to acquire support from China. When 22 militants were extradited to India from Myanmar on May 15, the militant leadership from the top 11 northeast rebel groups were not among them. There is evidence, according to an Indian source, that these rebel leaders are now in Yunnan, China, where they frequently seek medical attention and Chinese support.

Their cause is independence, which fits neatly into China’s goal to push India farther west. Northeast rebel chief Paresh Barua implied in 2018 that he gets support from China, and asserted that his relations with China are “very cordial”. He stated that China “can do certain things, but they cannot do everything for us.”

A still from an Arakan Army propaganda video. (Image by Rakharazu Media/Youtube)

A still from an Arakan Army propaganda video. (Image by Rakharazu Media/Youtube)

The conflict in the Rakhine and Chin states of Myanmar are of particular concern in India’s northeast as the Arakan Army is attacking government forces and Indian companies constructing a port and road through Myanmar that will be a second lifeline to the Seven Sisters. In the northeast, rebels frequently blow up gas pipelines.

According to Bhaumik, the surface-to-air missiles sold to the Arakan Army are China’s F-N6 MANPADS, capable of downing military helicopters and jets, as well as civilian airliners.

Another Indian expert said that the Arakan Army gets “everything from 7.62 caliber weapons to anti-aircraft guns of Chinese origin, which are easily available from black markets in Chiang Mai, Thailand.”

A government helicopter shot in February, likely by the Arakan Army, was forced to land. On board was the chief minister of Rakhine and other officials.

China does not supply weapons for free. The Arakan Army pays China’s front organizations in Southeast Asia for weapons, and Thai arms smugglers front for the Chinese, according to sources. China’s Norinco arms manufacturer uses these front organizations to sell to the Arakan Army, according to Bhaumik’s reporting.

(shutterstock.com photo)

(shutterstock.com photo)

Norinco did not respond to a request for comment. USINDOPACOM, the U.S. military headquarters for Asia, likewise did not respond.

In addition to China’s supply of funding and weapons, according to a military source, the Arakan Army obtains weapons and drugs from the Kachin and Wa armies. The latter has been described as recently as 2015 as a “narco-army” that obtains weapons, including heavy artillery, surface-to-air missiles, and armored vehicles, from China. Both armies reportedly have their own arms factories that produce Chinese-style weapons. The factories were purchased from China and are manned by Chinese technicians. The support from China has empowered the UWSA to defend a territory and maintain a ceasefire agreement with the Tatmadaw that has held for 31 years.

United Wa State Army (UWSA) soldiers participate in a military parade in Panghsang on April 17, 2019. The soldiers are shouldering MANPADS. (Photo by Ye Aung Thu/AFP)

United Wa State Army (UWSA) soldiers participate in a military parade in Panghsang on April 17, 2019. The soldiers are shouldering MANPADS. (Photo by Ye Aung Thu/AFP)

Training for the Arakan Army’s new MANPADS, according to a military source, was either from the KIA or the Chinese arms company. Sale of the MANPADS to the Arakan Army was “in response to [the] Myanmar Army using helicopters to fight Arakanese,” he wrote.

According to the source, China has “complete” influence over Kachin State. The think tank expert wrote that “the AA has been incubated by the Chinese using the KIA.”

The April 22 report in Eastern Link buttresses the case for a strong connection between China and the Arakan Army. “The AA is said to have strong links with China since its formation in Kachin in 2009,” writes Bhaumik. “Its spokesman Khaine Tukkha recently said ‘China recognizes us while India does not,’ which explains why AA does not disturb the Chinese deep seaport at Kyaukphyu but kidnaps and badgers Indian construction workers involved in the Kaladan project.”

The Arakan Army did not respond to multiple requests for comment.

On April 30 the Arakan Army did, however, deny allegations made by the Myanmar military that it produces and traffics enough methamphetamine with the Kachin-based Kaungkha militia to support itself financially. Tellingly, they remained silent on the April 22 report of a Chinese arms shipment.

Members of UWSA (United Wa State Army) in Poung Par Khem, near the Thai and Myanmar border on June 26, 2017.

Members of UWSA (United Wa State Army) in Poung Par Khem, near the Thai and Myanmar border on June 26, 2017.

China’s diplo-terror in South and Southeast Asia

“China has a strategic interest in maintaining a foothold inside Myanmar through the Wa, but also benefits economically through the exploitation of minerals in the Wa’s area that are exported across the border,” according to Lintner. “A well-armed UWSA that does not fight against Myanmar’s government is in China’s strategic interest, not least because it gives Beijing negotiating leverage in issues related to trade, investment and access to the Indian Ocean through the development of ports.”

China is blatant in using its support for ethnic militia groups to threaten the government. When addressing local concerns about a Chinese-backed copper mine, according to Lintner, a Myanmar government minister feared that China could retaliate against any trouble to the mine by supporting ethnic violence that would harm Myanmar’s economy.

An Indian source expressed a similar concern. If the country increases tension with China, it fears increased Chinese support for northeast militants. “Whenever China is politically upset with us, there will be clashes on the border as happened on May 5 and 9, there will be harboring of northeastern militants as we hear now and there will [be] a rise in China-supported Pakistan rhetoric,” said retired Lt-Gen John Mukherjee, a former chief of staff of India’s Eastern Army and now vice-president of a Calcutta-based think tank, to the Eastern Link.

An object lesson in diplo-terrorism is the leverage over Myanmar and India that China gained by arming the Arakan Army, operating in the corridor from northeast India over Myanmar’s Chin and Rakhine states to the Indian Ocean.

An aerial view of Rakhine State, Myanmar. (shutterstock.com photo)

An aerial view of Rakhine State, Myanmar. (shutterstock.com photo)

The evidence of China using violence by ethnic militias in Myanmar against its competitors demonstrates the violent side of its Belt & Road development project, which not only ensnares recipients in debt traps, but seeks to bar competitors through violent means deployed by criminal sub-state actors.

Reflecting its controversy, Belt & Road has gone through several name changes over its history, including the overlapping “Silk Road Economic Route”, “21st Century Maritime Silk Road”, “Belt and Road Initiative” (BRI), “One Belt, One Road” (OBOR), and “String of Pearls”.

China’s incentives to obstruct India’s infrastructure construction in Myanmar stem from its attempt to be at the center of Asia’s economy. The CCP is in competition for territory and influence with India throughout South and Southeast Asia, and seeks to sabotage India’s $484 million Kaladan project in Myanmar. The project includes a port at Sittwe, Myanmar, connected by river transport and a planned 109 km road to India’s border at Zorinpui. The project provides a second surface route for trade to India’s isolated northeast in case the Siliguri Corridor (also known as the “chicken’s neck”) were to be disrupted.

“China does not want Indian influence to increase in Myanmar,” according to an Indian source. “They want a monopoly.” While at first Myanmar was suspicious of China’s intentions, according to the source, they eventually decided they could get money for the military from a deal. “China pays people off in a huge, huge way,” he said. “That is their main strength.”

The think tank source sees China’s strategy as one to push its influence well south of its own border. “This strategy of supporting the AA has enabled the Chinese to expand its area of influence towards western Myanmar i.e. the India Myanmar border,” he wrote.

Several of the interviewed experts do not want the international community and potential sanctions over the Rohingya to force Myanmar’s government into the arms of China. “China is playing a multi-dimensional game in South Asia,” said the Australian academic. “China wants to weaken India. India is in a war with Pakistan, and does not want to make a new enemy of Myanmar.”

China and India compete in Myanmar

China has attempted to increase its influence in Myanmar over the past decades as both China and India have sought since at least 2008 to counter each other’s influence and acquire gas reserves off the coast of Rakhine State. The most recent offshore gas field was discovered in early 2020.

In a win for India, Myanmar agreed in 2009 to the Kaladan Multi-Modal Transit Transport Project (KMMTTP), which is the port, river and road construction in Myanmar designed to serve India’s Northeast.

China saw this Myanmar-India deal, along with Myanmar’s democratization in the early 2010s, as a threat to the influence it has built there since the 1960s. This was compounded by Myanmar’s 2011 cancellation of the Myitsone Dam, a joint project with the China Power Investment Corporation (CPI). Myanmar’s former information minister, U Ye Htut, argues that following the dam suspension and improved relations with the West, it was no coincidence that new ethnic armies and conflicts appeared in the north, and armed conflicts in the Shan and Kachin states intensified.

Myanmar protestors hold a rally in Yangon to protest against any reinstatement of a controversial Chinese-backed mega-dam on Jan. 18, 2020 during the final day of Chinese President Xi Jinping visit in Naypyidaw. (Photo by Sai Aung Main/AFP)

Myanmar protestors hold a rally in Yangon to protest against any reinstatement of a controversial Chinese-backed mega-dam on Jan. 18, 2020 during the final day of Chinese President Xi Jinping visit in Naypyidaw. (Photo by Sai Aung Main/AFP)

Analysts with whom I spoke argue that after the Kaladan deal, China sought to punish Myanmar and India by supplying and directing ethnic militias in the country, notably the Arakan Army, to increase the number and scale of attacks on the Tatmadaw, and on India’s road to the northeast.

According to one of the military sources: “The Chinese interest in the area is somewhere related to String of Pearls and domination of the Indian Ocean. Once they came to learn about the agreement by India and Myanmar, they too got into agreement with Myanmar and developed a nearby place into [a] port and subsequently Special Economic Zone (SEZ). Whereas on the other side they tried to disrupt the Indian project by [the] Arakan Army.”

A still from an Arakan Army propaganda video. (Image by Rakharazu Media/Youtube)

A still from an Arakan Army propaganda video. (Image by Rakharazu Media/Youtube)

The Arakan Army is a sub-state actor that utilizes terrorist tactics and has been labeled a terrorist organization by the Myanmar government. Creating a terrorist group near your development project to attack a competitor’s development project can be a double-edged sword. Analysts speculate that China paid protection money to the Arakan Army to speed its project through, but India did not, resulting in the delays for India’s Kaladan project.

China’s support to the Arakan Army did correlate with good relations that allowed it to build the $2 billion Kyaukphyu deep sea port, 100 km to the south of India’s port project at Sittwe, Myanmar. In 2009, China signed an MOU for the port and a railway connecting the port to China’s Yunnan province. A special economic zone (SEZ) was established, and gas and oil pipelines used to link the port to China’s Yunnan province were operational by 2013 and 2017 respectively. In 2017, a China-Myanmar Economic Corridor (CMEC) was agreed that could include the building of a road and finalization of the railway.

Chinese President Xi Jinping and Myanmar State Counsellor Aung San Suu Kyi hold talks during their meeting at the Presidential Palace in Naypyidaw on Jan. 17. (AFP photo)

Chinese President Xi Jinping and Myanmar State Counsellor Aung San Suu Kyi hold talks during their meeting at the Presidential Palace in Naypyidaw on Jan. 17. (AFP photo)

A Fujian government website that has since been deleted states that the Arakan Army and Shan State areas are important to what they call a “China-Myanmar New Strategic Corridor”. According to the cached site, “the Myanmar Government Army and the Arakan Army (AA) armed conflict area and the Shan State conflict area are the key areas of the China-Myanmar New Strategic Corridor. The strategy is of great significance and deserves high and continuous attention from Chinese personnel.” (缅政府军与若开军(AA)武装冲突区域及掸邦冲突区域系中缅新战略走廊的关键地段,战略意义重大,值得中方人员高度与持续关注。)

CMEC involved massive loans from China to Myanmar. But then Naypyitaw decreased its scope from $7.5 to $1.3 billion in 2018, angering Beijing. It’s alleged by my sources that China directed its Myanmar ethnic militias to increase attacks in retaliation for Myanmar’s decrease in scope of the Belt & Road project. Ethnic militias did in fact increase their level of violence substantially.

The Arakan Army’s roots in China

“So, the Arakan Army is basically funded by Chinese,” according to a military source. He estimated that 95 percent of the Arakan Army funding comes from China, though he said he did not have an exact figure. He said the remainder is from drug and weapon smuggling, as well as contributions from the Rakhines.

The Arakan Army also reportedly gets drug precursors from China. According to Bangladesh academic Iftekharul Bashar: “The raw materials for [Arakan Army] drug manufacturing are sourced from China via the UWSA controlled areas in Shan State.”

China’s alleged support of the Arakan Army against India’s construction in Myanmar was apparently quite effective. While the port at Sittwe, river dredging, and a river terminal at Paletwa were finished quickly, the last leg of the project, a 109 km road from Paletwa to the border with India, stalled amidst terrorist violence.

This photo taken on Jan. 28, 2019 shows residents holding bullet shells in a village in Rathedaung township, Rakhine State, where fighting between the Myanmar military and ethnic Arakan Army (AA) took place from Jan. 26 to 28. (AFP photo)

This photo taken on Jan. 28, 2019 shows residents holding bullet shells in a village in Rathedaung township, Rakhine State, where fighting between the Myanmar military and ethnic Arakan Army (AA) took place from Jan. 26 to 28. (AFP photo)

The $220 million road contract was awarded to the Delhi-based contractor, C&C Constructions, in June 2017. The Myanmar government then delayed the requisite clearances until January 2018. Once construction was underway, the Arakan Army kidnapped crews including Indian citizens, fire fighters, a Myanmar member of parliament, and sabotaged a vehicle and building materials. One of the Indian citizens died in captivity from “heart attack because of shock from the kidnapping,” according to a military source. The kidnapping included a retired Indian colonel and a bureaucrat representing C&C Constructions. The Indian government had to negotiate with the Arakan Army to get the survivors released.

The Arakan Army’s ability to deploy violence against the Indian project has been demonstrated along its entire length, including not only the road from India’s border to the Kaladan River, but along the river, and past the port into offshore waters. In late October, an Arakan Army boat intercepted a ship off western Myanmar and detained dozens of passengers, including soldiers and policemen.

According to one of the military sources, China provides speed boats to the Arakan Army, which they use to patrol the Kaladan River.

The Australian academic said: “The Chinese fishermen who are terrorizing the South China Sea are also in the Andaman Sea and [part of the] Bay of Bengal, trafficking drugs in addition to fishing.”

Local fishermen are unhappy with China’s Myanmar port, according to another source.

“The formation of the Arakan Army coincides with the [Myanmar-India] agreement” to build the port and road at Kaladan, a military source wrote. A Chinese military website also puts the founding date of the Arakan Army at 2009, the same year that Myanmar inked the deal on India’s Kaladan project.

The Arakan Army has deep backup and strategic depth well past its apparent focus on India’s development project in Myanmar. AA is a member of a UWSA-led alliance, as well as the smaller Brotherhood Alliance, which includes the TNLA and the Myanmar National Democratic Alliance Army.

Both the Arakan Army and TNLA are highly mobile, do not hold territory, and utilize hit-and-run tactics that make them hard to target through conventional military means. This puts the civilian population in their areas of guerrilla operation at risk of increased ethnic cleansing and mass detention should the Tatmadaw choose to expand upon their already ruthless counter-insurgency tactics.

This photo taken on Feb. 21, 2019 shows an unexploded ammunition lying on a field in Rathedaung township after fighting in Rakhine State between the Myanmar military and the Arakan Army. (AFP photo)

This photo taken on Feb. 21, 2019 shows an unexploded ammunition lying on a field in Rathedaung township after fighting in Rakhine State between the Myanmar military and the Arakan Army. (AFP photo)

India’s dilemma: Use force or pay protection

Both the Arakan Army and TNLA were founded in 2009. The Arakan Army has 7,000-8,000 rebel fighters, and the TNLA has 5,000. Arakan Army leaders are young and dynamic as opposed to the entrenched and commercialized old guard of most of the other rebel groups. They started fighting in earnest against the Tatmadaw in 2015 in Shan State, which is populated by ethnic Chinese.

The Arakan Army espouses an ideology of ethno-nationalism. When they strengthened sufficiently, they moved from Shan State to the Rakhine and Chin states, where they received support from the area’s majority-Buddhist population.

▶️Recruits train to fight in the Arakan Army, an insurgent group, in Myanmar's Kachin state.

— The Voice of America (@VOANews) October 17, 2019

👉The Arakan Army formed in 2009 and is currently fighting in Rakhine State, home of the Rohingya, against Myanmar government forces.https://t.co/UBLPJ4IlLk pic.twitter.com/bt426wCzL0

India’s Kaladan road is planned to pass through the hilly regions and dense forests of Chin State, making it an easy target for the Arakan Army’s hit-and-run tactics against C&C Constructions. “The company lobbied for strong military action and the Indian army conducted Operation Sunrise last year to demolish the Arakan Army's bases in [India’s] southern Mizoram,” according to Bhaumik. “The Indian army formally accepted in a press statement that the operation was necessary to tackle the Arakan Army which has 'emerged as a threat to the Kaladan project.’"

Operation Sunrise was conducted in coordination with the Tatmadaw. Instead of subduing the Arakan Army, however, the AA responded with greater force.

A still from an Arakan Army propaganda video. (Image by Rakharazu Media/Youtube)

A still from an Arakan Army propaganda video. (Image by Rakharazu Media/Youtube)

Some Indian military planners and the Tatmadaw want the two countries to further cooperate against the Arakan Army in Rakhine and Chin states. They argue that the rebels would then stop threatening the Kaladan project, which could be completed.

Others argue that such involvement may just invite retaliation from the rebels in addition to whatever they might be doing at the behest of China. India’s need to complete the Kaladan project is weighed against not getting drawn into a long and costly conflict in Myanmar. “That the Arakan Army is no throwaway weighs heavy on Indian military planners: They want to back the Tatmadaw so that it can regain control over the rebels in Rakhine,” writes Bhaumik. “The Kaladan project can then be completed. But India wouldn’t want to get too deeply involved. It can then avoid retaliation by the rebels. Military officials and strategic analysts have advised caution, saying India should avoid getting involved in the Rakhine imbroglio.”

The example of India’s peacekeeping force in Sri Lanka does not bode well for another intervention in Myanmar. Many Indians lost their lives in Sri Lanka, and the Tamil Tigers retaliated by assassinating India’s Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi in 1991. When C&C went bankrupt, according to Bhaumik, it was suggested that a new contractor be chosen that might pay protection money to the Arakan Army and thus get the project done.

Terrible fighting from early morning in Patherkilla (Mrauk U). Listen to the audio below. Fighting between Arakan Army & #Myanmar military. Several #Rohingya injured and 2 or 3 dead including a child. pic.twitter.com/xE0oiVrq2w

— Shafiur Rahman (@shafiur) February 29, 2020

"Mizoram chief minister Zoramthanga recently told this writer that he has asked PM Modi and foreign minister S. Jaishanker to appoint a new contractor for the Kaladan project because C&C has gone bankrupt. 'They (C&C) have no idea how to do business in this area. Rakhine is not Indian territory and the Indian army can't do much. I have asked Delhi to appoint a new contractor who can then be properly advised,' Zoramthanga said, hinting that the new contractor can be put in touch with the Arakan Army and could pay up to buy peace," according to Bhaumik in his report.

Bhaumik has been able to communicate directly with the Arakan Army. He wrote that “The Arakan Army has maintained it is not against trans-national projects in Rakhine, provided they ‘recognize’ AA and don't cooperate with the Burmese military.”

However, there are obvious dangers to recognizing and funding terrorism with protection money. It could incentivize yet more terrorism against India, and it could harm relations between India and Myanmar. Once the road is complete, the Arakan Army could demand “toll” for its use. The government of Myanmar, if angered by Indian protection money paid to AA, might very well do as much harm to the Kaladan project with a stroke of a pen, as can the Arakan Army with its entire store of Chinese weapons.

(shutterstock.com photo)

(shutterstock.com photo)

9th Arakan Army Day on April 10, 2018

9th Arakan Army Day on April 10, 2018

China’s ‘forward defense’ against India through the UWSA and Arakan Army

The biggest of China’s ethnic rebel groups is the UWSA, under which the Arakan Army serves in a coalition. China supports the UWSA, and in turn, the UWSA provides arms and ammunition to a large number of the ethnic rebel groups throughout Myanmar. Perhaps as a result of the influence that these Chinese arms produce, the UWSA leads an umbrella group for about 80 percent of the country’s ethnic rebels.

Called the Federal Political Negotiation and Consultative Committee (FPNCC), the group includes the KIA, the Myanmar National Democratic Alliance Army, the TNLA, the Arakan Army, the National Democratic Alliance Army, and the Shan State Army.

Of these groups, the Arakan Army is the fastest growing. “In 10 years — they grew to 8,000 people,” said Bhaumik. “The KIA took 40 years to reach 8,000.”

The KIA gets less support from China because it is Christian, and the CCP does not trust Christians, according to information attributed to John Mukherjee, former chief of staff of India's Eastern Army.

Neither does the CCP give significant support to the Muslim Rohingya’s small group of ARSA militants, according to the Australian academic.

China has not only armed the UWSA, but provided it with a safe haven and rear area for tactical retreat. The UWSA is not in direct conflict with the Tatamadaw currently, according to Lintner, but it is using a strategy of “forward defense” that involves arming other ethnic groups in Myanmar and thereby expanding its influence and tying down Myanmar’s military.

Government troops cross a bomb-damaged bridge outside the compound of the Gote Twin police station in Shan State on Aug. 15, 2019, after it was attacked by an ethnic rebel groups. (AFP photo)

Government troops cross a bomb-damaged bridge outside the compound of the Gote Twin police station in Shan State on Aug. 15, 2019, after it was attacked by an ethnic rebel groups. (AFP photo)

The UWSA grew from and holds most of the 20,000 square-km territory in Shan State previously controlled by the once-powerful Communist Party of Burma (CPB). Since the 1960s, China supported first the CPB, and then the UWSA, including through volunteer fighters and workers from China, political education in China, and Chinese military and engineering advisors.

The UWSA’s finances are controlled by ethnic Chinese businessmen. One of those businessmen, Wei Xuegang, “has massive investments in jade mines in Kachin State and other business ventures throughout the country,” according to Lintner. “In that capacity, he is close to many senior Myanmar military officers.”

United Wa State Army (UWSA) soldiers participate in a military parade in Panghsang on April 17, 2019. (Photo by Ye Aung Thu/AFP)

United Wa State Army (UWSA) soldiers participate in a military parade in Panghsang on April 17, 2019. (Photo by Ye Aung Thu/AFP)

Most Wa speak Chinese, use Chinese currency, and communicate over Chinese cell phone networks. Within its territory live approximately 600,000 people, including approximately 100,000 Chinese and other migrants. It has as many as 30,000 troops, 20,000 auxiliaries, and 2,500 police officers. The UWSA is equipped with Chinese armored vehicles, heavy artillery, and surface-to-air missiles. The army’s political arm includes a single political party and organization led by a nine-member standing committee of the politburo over a party membership of 10,000 individuals.

United Wa State Army (UWSA) special force snipers participate in a military parade, in Panghsang on April 17, 2019. (Photo by Ye Aung Thu/AFP)

United Wa State Army (UWSA) special force snipers participate in a military parade, in Panghsang on April 17, 2019. (Photo by Ye Aung Thu/AFP)

On April 20, a report detailed how China’s crime networks were collaborating with Myanmar’s armed ethnic groups to build huge enclaves in Myanmar’s Karen State. These “special economic zones” include casinos, condominiums and hotels. “In total, 157 square kilometers of Burmese territory have fallen under control of Chinese enterprises tied to gambling, money laundering, cryptocurrency, and even criminal networks,” according to the authors. They mention that China’s organized crime, or triads, are expanding in Karen State and threatening the peace process. Three deals claim to have a total capital investment of $36 billion, which the Chinese investors project to increase in value to $202.2 billion by 2027.

China’s embassy in Myanmar, and Myanmar’s Foreign Ministry, did not reply to requests for comment.

In addition to the most recent shipment of MANPADS to the Arakan Army, China previously supplied FN-6 MANPADS to TNLA rebels in Myanmar’s northeast. A cache of weapons seized after a November clash with the TNLA included a MANPADS, 150 small arms and 80 sacks of explosives.

The deadly surface-to-air munition may have come from China via the UWSA, which has fielded MANPADS since at least 2000. The FN-6 entered the UWSA arsenal in about 2012, and has a 6-km range, high decoy resistance, and a digital infra-red homing system. Each FN-6 costs approximately $60,000 to $90,000, making them affordable to only the wealthiest drug dealers, or those militias with state backing. Apparently due to a Chinese veto, the weapon has not until recently been released to ethnic militias in Myanmar other than the UWSA.

First Surface-to-Air missile live fire exercise between China and Thailand

Monakhali Beach, where the FN-6s were reportedly dropped for the Arakan Army, is in Bangladesh’s Chittagong Hill Tracts, about 10km across a nature preserve from the Myanmar border. The weapons landed in Bangladesh on Feb. 21.

According to Bhaumik, the Bangladesh military failed to adequately patrol the area.

“Nearly 150 Rakhine porters drawn from various villages of Chittagong Hill Tracts in Bangladesh and accompanied by 50 fighters of [the] Arakan Army carried this consignment on foot and mules through Gundum and Rejupara, Uhalapalonh and Paglirara crisscrossing the very hilly border region. Skirting the Matamuhuri-Sangua wildlife sanctuary, the column skirted Singpa and reached the Arakan Army camp at Sandak (Mro) near Thanchi on March 2.”

An Indian source questioned how the weapons could land on a beach that is covered by Bangladesh Navy and Coast Guard. He said the Bangladesh Navy is corrupt and that it takes large “bribes from smugglers who land contraband including drugs on this coastal stretch and allow them to operate." He believes it is likely that Arakan Army smugglers paid off the Bangladesh Navy, which can arrange for patrol schedules to change.

The Bangladesh Navy and the Bangladesh Foreign Ministry did not immediately reply to a request for comment.

India has tried to counter China’s influence in Myanmar for decades. In 2007, India indicated that it would supply arms to Myanmar to combat Indian insurgents who had bases on the Myanmar side of the border. In 2019, Operation Sunrise targeted Arakan Army bases near the Indian state of Mizoram, and conducted operations against it and other militant groups. Several Arakan Army bases were destroyed, but Indian forces then had to pull back for redeployment against insurgencies in other parts of the northeast.

“After carrying the huge consignment to Sandak (Mro), the AA has smuggled the arms into Rakhine using the Parva corridor in South Mizoram [where] the local Khumi villagers are friendly to the insurgents,” wrote Bhaumik.

China’s Norinco arms manufacturer does not sell directly to the Arakan Army, but rather does so through middle men, according to sources and reporting. In 2019, Myanmar’s top General, Min Aung Hlaing, confirmed that China is indirectly supplying arms to the country’s ethnic rebels. To more effectively extricate Myanmar from China’s influence, the general is seeking to diversify his own sources of military hardware.

Bhaumik wrote that, “the Chinese state-owned ordnance company Norinco supplies non-state actors like [the] Arakan Army using some fronts. They have done these for northeast Indian rebels in the past.” According to an expert that Bhaumik interviewed, China’s Norinco arms manufacturer has a front organization called TCL, that “loaded the consignment on a ship at Heibei, a small fishing port in South China in the early part of February.”

He wrote that “A TCL manager Lin who also goes by the name of Yuthna was [instrumental] in loading the cargo on the ship. It is not clear whether the AA has paid TCL or whether the Chinese intelligence would have organized covert payment.”

According to India’s The Telegraph, Yuthna and TCL were also involved in a 2010 attempted arms deal with rebels in northeast India. The arms included $1 million worth of “AK-series automatic rifles, light machine guns, rocket launchers, rocket-propelled grenades and five lakh [500,000] rounds of ammunition,” according to The Telegraph, and were to be shipped from southern China via a Chinese shipping company in Bangkok. The arms were to undergo mid-ocean ship-to-ship transfer to fishing trawlers to reach Bangladesh, then delivered overland to India according to an Indian official. The payment was allegedly made through a bank branch in an African country. The end-user certificate came from Laos.

The think tank analyst confirmed Norinco’s involvement, noting that the front is associated with China’s People’s Liberation Army (PLA). “The supply of weapons comes from the NORINCO factories in Yunnan,” he wrote. “TCL, a NORINCO front owned by a retired Maj. Gen. Xin Ling of [the] PLA, registered in Macao, loaded the consignment on a fishing trawler at Heibei, a small shipping port in south China in the early part of February.”

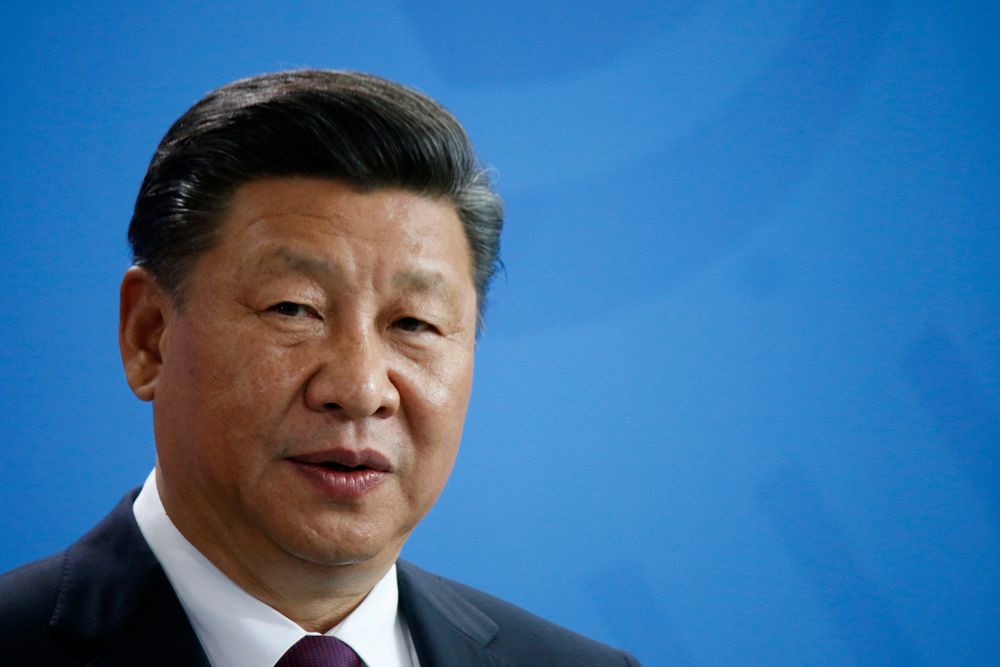

A 2017 file image of Chinese President Xi Jinping. (shutterstock.com photo)

A 2017 file image of Chinese President Xi Jinping. (shutterstock.com photo)

China’s other support for terrorism

“Some foreigners who have eaten their fill have nothing better to do than point fingers at us,” Xi Jinping said in 2009 when he was vice-president. “We don’t export revolution, poverty or hunger, and we don’t cause you any trouble, so what is there for you to complain about?”

China’s decades of support for terror groups in Myanmar says otherwise, as does its support to other terrorists and state sponsors of terrorism globally. “China, in fact, holds the key to the availability of weapons and ammunition among the terror groups in northeast India that is actually keeping insurgency alive in this far-eastern frontier,” Wasbir Hussain wrote in 2015.

China not only funds the UWSA and Arakan Army in Myanmar, and rebels in northeast India, but pressures the Seven Sisters through direct military attacks, often by unarmed soldiers in the state of Arunachal Pradesh, and by military incursions against nearby Bhutan, which is under India’s protection according to a 1949 treaty.

China’s ally Pakistan also pressures India by publicly supporting violence in the India-controlled part of Kashmir. In response, India imposed direct federal rule on the autonomous region in August 2019.

Both China and Pakistan support Taliban insurgents against the NATO-backed government in Kabul. China has reportedly paid protection money to the Taliban insurgents in Afghanistan in order to maintain its trillion-dollar copper mine there.

China’s support to the Arakan Army, accused of acts of terror and drug running in Southeast Asia, is the latest incidence of Beijing’s diplo-terrorism meant to leverage its neighbors through support of violent sub-state actors, pseudo-states, insurgencies, thieves, arms smuggling, and gambling operations.

Sadly, China’s conception of its role in the world seems to be guided by exactly the zero-sum conflict over territory and influence that it accuses others of fomenting. It does not limit itself to soft power. Rather, Beijing associates with the lowest-level forms of terrorist and gangland violence in order to attain its diplomatic objectives.

As Aesop said in the 6th century BCE:

“A man is known by the company he keeps”

The same applies to nation-states.

Anders Corr holds a Ph.D. in government from Harvard University and has worked for U.S. military intelligence as a civilian, including on China and Central Asia. The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official editorial position of LiCAS.news

© Copyright 2020 LiCAS.news

This article was published May 28, 2020.