Church program helps poor meet food needs during pandemic

Program gives more purchasing power to poor families while helping to protect them from COVID-19

Amid the pandemic, people in a poor district in the Philippine capital are finding better options for their food source, thanks to a community-based church program.

One day, a woman was trying to decide whether to buy corn or squash. She ended up buying both.

“If I was at the market, I could not take both because I don’t have enough money,” she told another lady next to her.

They were outside a Catholic chapel in a village in the outskirts of Manila where a vehicle filled with fresh vegetables was parked.

It was part of a Basic Ecclesial Community (BEC) project amid the strict quarantine measures imposed by the Philippine government due to the coronavirus pandemic.

Members of the Basic Ecclesial Community in the Sanctuario de San Vicente de Paul parish unload vegetables purchased directly from farmers in a nearby province. (Photo by Mark Saludes)

Members of the Basic Ecclesial Community in the Sanctuario de San Vicente de Paul parish unload vegetables purchased directly from farmers in a nearby province. (Photo by Mark Saludes)

Each community has about 200-member households that are divided into smaller groups of 10 to 15 households with their own time to buy the farm produce.

“Most households have already pre-ordered the vegetables,” said Marissa Tinao, a BEC leader.

The parish purchased the vegetables directly from farmers in Nueva Ecija province, north of Manila.

Tinao said that even before the coronavirus outbreak, the Christian community has been planning to initiate the project as part of its “food security program.”

When the government placed the national capital under lockdown in March, the BEC and the parish immediately focused on relief distribution.

They were able to provide food packs to more than 600-member households for three months.

“But we cannot always rely on relief goods,” said Tinao.

A church office in the Sanctuario de San Vicente de Paul parish serves as trading station for fresh vegetables to the community. (Photo by Mark Saludes)

A church office in the Sanctuario de San Vicente de Paul parish serves as trading station for fresh vegetables to the community. (Photo by Mark Saludes)

In mid-June, BEC leaders convened to plan how to provide continuous supply of rice and vegetables to Catholic communities at a fair price.

Lita Asis-Nero, BEC coordinator of the parish, said the lockdown affected the purchasing power of many families, especially the poor.

“Workers have been displaced and many household heads lost their jobs because of the prolonged quarantine,” said Asis-Nero.

The situation compelled the communities to look for ways to help families strengthen their purchasing power while battling the pandemic.

At least ten families loaned their savings to the BEC as initial capital.

“We were able to collect at least US$1,600, which we used in buying vegetables,” said Asis-Nero.

From its emergency funds, the parish let the BEC borrowed about US$7,000 to purchase at least 250 sacks of rice that are sold to the communities at a lower price than in the market.

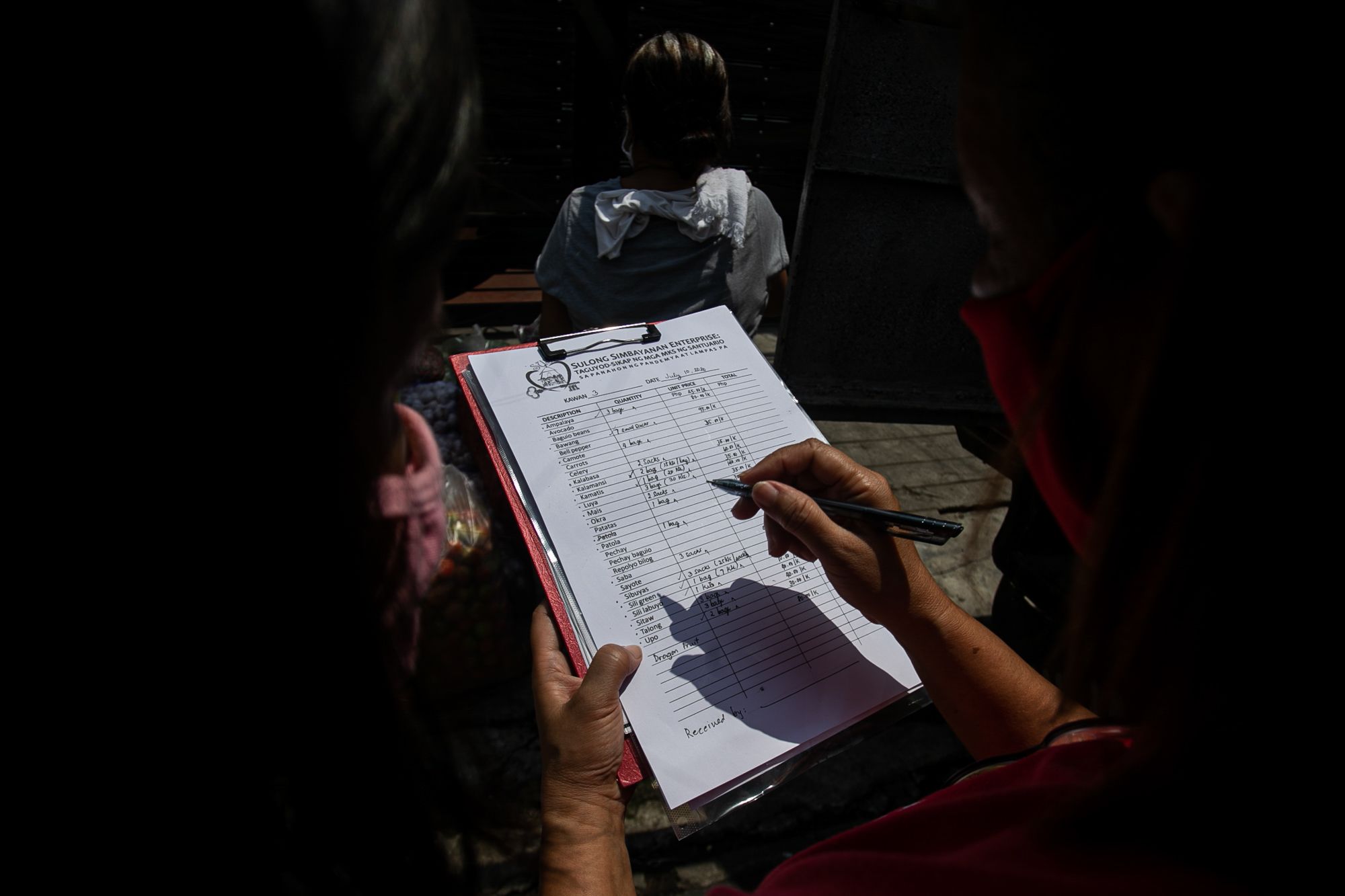

Volunteers sort out the vegetables and pack them based on the list that community members submitted. (Photo by Mark Saludes)

Volunteers sort out the vegetables and pack them based on the list that community members submitted. (Photo by Mark Saludes)

Asis-Nero said they also made sure that farmers are not exploited in their transactions.

“We let them set their price and we pay them the right amount,” she said.

“We can sell the goods at a lower price because purchasing them directly from the source cuts the commission of the middle man or the trader,” she said.

The BEC sells the vegetables at the lowest possible price to help poor families in the community. (Photo by Mark Saludes)

The BEC sells the vegetables at the lowest possible price to help poor families in the community. (Photo by Mark Saludes)

The BEC has also lower overhead cost “because the whole community helps in managing and handling the program without the need to pay for personnel.”

“It is a community-managed enterprise that addresses community concerns on food, health, and other resources,” said Asis-Nero.

The program allows residents to avoid congested public markets where authorities placed a coffin to warn the public of the danger of COVID-19. (Photo by Mark Saludes)

The program allows residents to avoid congested public markets where authorities placed a coffin to warn the public of the danger of COVID-19. (Photo by Mark Saludes)

The project primarily aims to address the needs of BEC members in the parish, but other community members are welcome to avail of the produce on a “first-come-first-serve” basis.

Helen Reyes, a 33-year-old resident of Upper Banlat in Tandang Sora village, got her one-week supply of vegetables and rice from the BEC.

Reyes said the community-initiated project addresses the problem of COVID-19 transmission in crowded public markets.

Entry to the office is controlled to follow community quarantine protocols. (Photo by Mark Saludes)

Entry to the office is controlled to follow community quarantine protocols. (Photo by Mark Saludes)

“I’ve been avoiding the wet market since last month after I saw news reports that some public markets had to close down due to a number of COVID-19 cases,” she said.

“As much as possible,” she said she buys food from ambulant vendors and from neighbors “to lessen my exposure to crowded places.”

Reyes lives with her parents who are both septuagenarian and deemed high-risk to COVID-19 infection.

Two weeks ago, local government units have temporarily closed down public markets in the capital after some vendors were found positive with the disease.

Authorities said the markets will reopen as soon as they get the results of the swab tests of vendors and workers to ensure public safety.

Social distancing is a challenge in most public markets due to the influx of people. (Photo by Mark Saludes)

Social distancing is a challenge in most public markets due to the influx of people. (Photo by Mark Saludes)

On July 14, Dr. Rabindra Abeyasinghe, World Health Organization Philippine representative, said it is imperative “to determine the event and activities” where COVID-19 transmission is happening.

The health expert said a “speedy contact tracing” would help the country’s “improved testing capacity” in arresting the spread of the disease in public places.

The threat of coronavirus community transmission is far from over said Asis-Nero.

“That’s why Catholic communities in parishes must step up to battle these threats,” she said.

The BEC of the San Vicente de Paul parish “plans to institutionalize” the project that “gives more purchasing power to poor families while protecting us from the disease.”

Asis-Nero said the parish is already planning to present the idea to the Diocese of Novaliches to “encourage other parishes and vicariates to replicate the program.”

Published July 24, 2020

© Copyright MMXX LiCAS.news

A volunteer sprays disinfectant on a visitor to the market. (Photo by Mark Saludes)

A volunteer sprays disinfectant on a visitor to the market. (Photo by Mark Saludes)

Some public markets in Metro Manila have temporarily closed down after several vendors were tested positive with the new coronavirus disease. (Photo by Mark Saludes)

Some public markets in Metro Manila have temporarily closed down after several vendors were tested positive with the new coronavirus disease. (Photo by Mark Saludes)

Close contact is also a challenge in public markets due to limited space. (Photo by Mark Saludes)

Close contact is also a challenge in public markets due to limited space. (Photo by Mark Saludes)

A vendor wears an improvised face shield. (Photo by Mark Saludes)

A vendor wears an improvised face shield. (Photo by Mark Saludes)

A meat vendor wears a mask to meet the minimum health standards implemented in public markets. (Photo by Mark Saludes)

A meat vendor wears a mask to meet the minimum health standards implemented in public markets. (Photo by Mark Saludes)

Some vendors are allowed to sell outside the market to minimize the crowd inside. (Photo by Mark Saludes)

Some vendors are allowed to sell outside the market to minimize the crowd inside. (Photo by Mark Saludes)