EARTH DAY 2022: No more vegetables in the market?

Changing weather has halved the amount of produce arriving at markets in Manila. A Catholic priest, his "drug reformists" and women farmers may have a solution in their "Saklay" farm

Midnight calm envelops the public market in Balintawak district in the outskirts of the Philippine capital Manila. The heaps of fruits and vegetables on display conceal a crisis brought about by climate change - less than half of the usual produce are arriving and those that do are rotting sooner.

Like any other market, it is supposed to be busy. But even as the country’s economy tries to recover from the coronavirus pandemic, the nights in Balintawak have gone quieter compared to before.

Cathy Leonardo has been selling vegetables in the market since she was eight years old. Almost three decades have passed, and she’s still here, buried 14 hours daily behind stacks of her summer bestsellers — moringa flowers and leaves, bilimbi fruits, and birch flowers.

This week’s supply of vegetables is sourced from the province of Batangas, south of Manila. Cathy expects that other varieties will arrive soon.

“I can’t wait to sell all this,” she says, pointing to the stack of moringa flowers. “It’s been raining the past weeks, so the supply is short, and they’re already turning black.”

Cathy Leonardo tending to her stall at the public market in Balintawak district in the outskirts of the Philippine capital Manila. (Photo by Marielle Lucenio / LiCAS.news)

Cathy Leonardo tending to her stall at the public market in Balintawak district in the outskirts of the Philippine capital Manila. (Photo by Marielle Lucenio / LiCAS.news)

It’s the peak of summer in the Philippines, but two tropical storms have already passed in just a week, leaving about 200 people dead and a swath of destruction in the central part of the country.

The Philippines faces at least 20 tropical cyclones every year, destroying properties and businesses worth about US$1 billion annually, according to the Finance department in 2021.

The agriculture sector, which makes up 10 percent of the country’s economic output, is one of the most affected by the disasters.

Market traders in the public market in Balintawak disctrict, Manila, preparing their stalls in the early hours of the day. (Video by Marielle Lucenio / LiCAS.news)

Market traders in the public market in Balintawak disctrict, Manila, preparing their stalls in the early hours of the day. (Video by Marielle Lucenio / LiCAS.news)

Changing weather, lesser harvest

Parked near Cathy’s stall are “jeepneys” and trucks ready to unload vegetables from the provinces.

“That’s it for today,” John Paul Samson, a driver, shouts at one of the stall owners.

The 23-year-old John Paul has traveled from Norzagaray town in Bulacan province for about two hours to deliver vegetables to Balintawak.

This evening, he unloads broccoli, which occupied almost a third of his vehicle. It’s about a ton of vegetables, but for John Paul it’s much less than what he used to bring to the city.

“Three years ago, we had to travel twice or thrice to bring in all the harvest, but starting when the summer became hotter and the rainy days longer, we can barely fill the whole jeep,” he says.

“Jeepney” loaded with vegetables from the provinces. (Photo by Marielle Lucenio / LiCAS.news)

“Jeepney” loaded with vegetables from the provinces. (Photo by Marielle Lucenio / LiCAS.news)

John Paul’ hometown, Norzagaray, is located near a big dam, but farmers experience a shortage of water especially during the dry season in March, April, and May.

“Broccoli can be a sensitive plant to grow, especially because it needs a lot of water,” he says. “Unfortunately, we just depend on rain for water.”

Then the rain came early this month, and it poured. “There was just too much of it,” says John Paul. The crops were flooded, and a week later, the pests came.

A study conducted by the World Food Programme last year listed the province of Bulacan as one of the provinces most exposed to flooding risks.

Climate-related hazards are expected to continue to have “substantial impact” on agriculture, livestock, and fishery supply chains in the coming years, said the study.

A family relaxes together at the market before the day's trade begins. (Photo by Marielle Lucenio / LiCAS.news)

A family relaxes together at the market before the day's trade begins. (Photo by Marielle Lucenio / LiCAS.news)

Shifting to ‘sustainable agriculture’

A Catholic priest in the province of Nueva Ecija, farther north of Bulacan, has been trying to mitigate the impact of the changing weather patterns on agriculture.

“We’re trying to grow vegetables that will survive the inconsistent climate so that the livelihood of our people will not be badly affected,” says Father Arnold Abelardo, a Claretian missionary.

The priest heads the “Ako ang Saklay” community, literally “I am the crutches,” that was established in 2014 to help women farmers find an alternative source of livelihood.

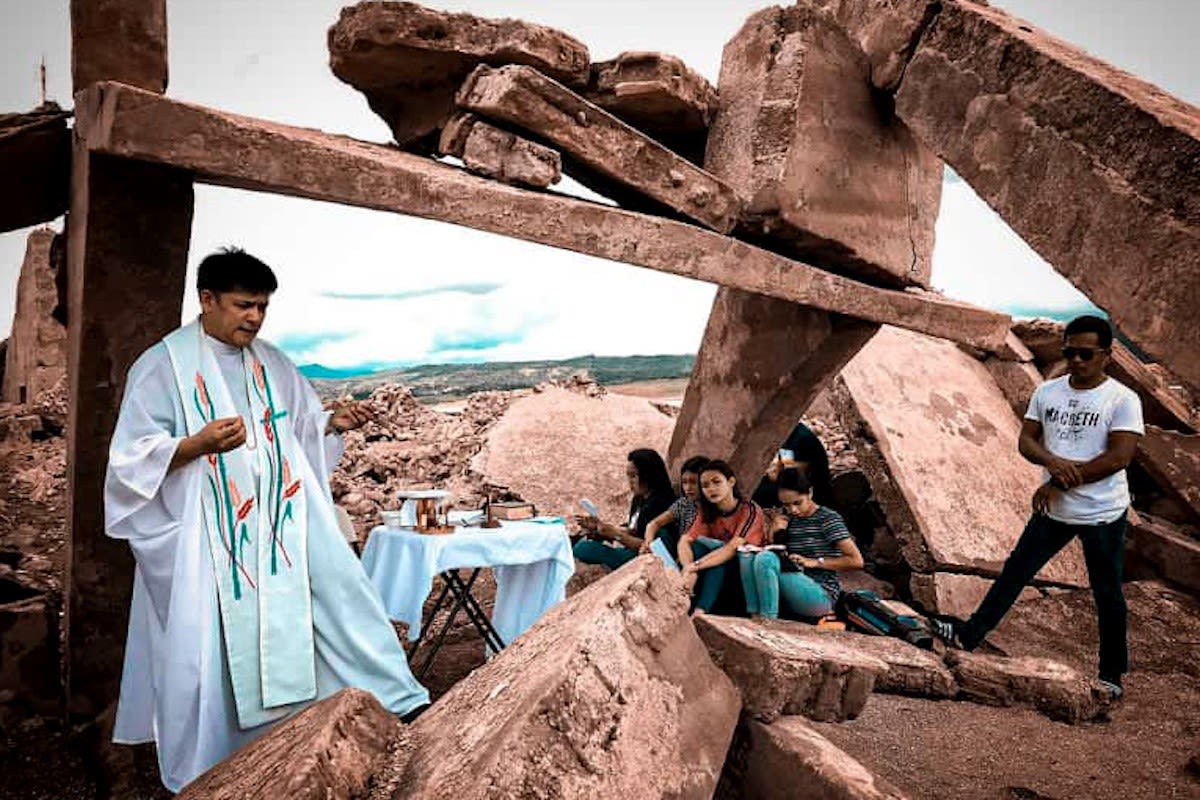

Father Arnold Abelardo, CMF, celebrates Mass at the ruins of a church in the sunken town of Pantabangan in the northern Philippine province of Nueva Ecija. (Photo supplied)

Father Arnold Abelardo, CMF, celebrates Mass at the ruins of a church in the sunken town of Pantabangan in the northern Philippine province of Nueva Ecija. (Photo supplied)

The community caught the attention of the media starting 2016 when Father Abelardo started giving sanctuary and counseling to drug dependents in the middle of the government’s “war on drugs.”

Today, the priest’s “drug reformists” are working with the women farmers in growing varieties of vegetables in the “Saklay” farm.

“The land feels the impact of climate change,” says Father Abelardo. “Our watermelons are not growing as they used to be,” he says, adding that they have to “diversify our crops.”

With the help of aid agencies, the priest has started growing oyster mushrooms.

“You can just let it grow inside your house,” he says. “It doesn’t need much space, and is less prone to calamities.”

“We have to shift our focus into projects that are sustainable to survive,” says the missionary priest.

The public market in Balintawak district in the outskirts of the Philippine capital Manila. (Video by Marielle Lucenio / LiCAS.news)

The public market in Balintawak district in the outskirts of the Philippine capital Manila. (Video by Marielle Lucenio / LiCAS.news)

‘Now or never’

The latest Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change report notes that it is “almost inevitable” that global warming will breach 1.5 degrees Celsius and greenhouse gas emissions will peak by 2025.

The report suggests a dramatic shift to cleaner energy, including the phase out of coal, low-carbon investments, more forests and soil preservations, and the adaption of new technologies to produce clean energy.

“It’s now or never, if we want to limit global warming to 1.5C,” said Jim Skea, a professor at Imperial College London and co-chair of the working group behind the report.

“Without immediate and deep emissions reductions across all sectors, it will be impossible.”

The Philippines has only 0.3% share of the world’s total greenhouse gas emissions, but it is the second most vulnerable country in the world to climate change, according to the 2020 global climate risk index.

“People are taking action,” says Virginia Benosa-Llorin, Greenpeace campaigner in the Philippines, adding that the government “failed to rise up to the challenge of the climate crisis.”

The Philippines’ Commission on Human Rights has recently concluded, after an investigation, that people affected by climate change and whose human rights have been dramatically harmed must have access to remedies and access to justice.

For Cathy, however, her fight this evening is about the humidity inside her stall in Balintawak’s market, and the money that she will bring home.

All the talk about the changing weather patterns are alien to her. What she knows is, “It’s different now.”

“About this time in the past, you might not be able to talk with me because of the crowd,” she says.

“Now, the market is rarely packed. I think it’s because of the prices of the produce. People would rather buy something else.”

It’s past midnight and Cathy says it was a lousy day for her.

In the good old busy days, she would earn between US$50 and US$100. Tonight, however, she says she would be lucky to bring home US$10.

Produce at the public market in Balintawak district in the outskirts of the Philippine capital Manila. (Photo by Marielle Lucenio / LiCAS.news)

Produce at the public market in Balintawak district in the outskirts of the Philippine capital Manila. (Photo by Marielle Lucenio / LiCAS.news)

With generous support from missio Aachen

and

Text and photos by Marielle Lucenio, Philippines

Published April 22, 2022

© Copyright MMXXII LiCAS.news

A market stall in Balintawak district in the outskirts of the Philippine capital Manila. (Photo by Marielle Lucenio / LiCAS.news)

A market stall in Balintawak district in the outskirts of the Philippine capital Manila. (Photo by Marielle Lucenio / LiCAS.news)