Malaysian civil service incompetence is a punishing lesson for students

As the pandemic rolls on, the country struggles to keep its education system running

As Malaysia lurches from one coronavirus lockdown to another, the problem of educating the nation’s youngsters becomes ever more acute.

There are almost 2 million children in primary and secondary education nationwide, with an additional 700,000 in higher education. And they are suffering.

In March last year, the government closed all education facilities and — like many countries around the world — tried to move lessons online with varying degrees of success. Yet, as time went on two major flaws exposed chronic weaknesses in the system.

First, and oft talked about, Malaysia’s education system has become a haven for the lazy, weak-minded, incompetent and, in some cases, criminal. Accountability and transparency? That’s pie in the sky talk. It is a common joke that the country will freeze before a civil servant in the education system will lose his or her job.

So, when the ministry in its infinite wisdom made lessons voluntary during the lockdown, some diligent educators took to online learning with gusto, marshalling their students and trying their best to continue with the curriculum.

However, a significant minority of teachers shut up shop and took a three-month paid holiday.

Students have their temperature taken at a school Kota Kinabalu, Sabah, Malaysia on Aug. 21, 2020. (Photo by Sharif Putra/shutterstock.com)

Students have their temperature taken at a school Kota Kinabalu, Sabah, Malaysia on Aug. 21, 2020. (Photo by Sharif Putra/shutterstock.com)

The second factor was arguably more crucial — access to the internet. News reports of children in poorer families huddled around one mobile phone or time-sharing to glean what information they could from teachers became commonplace. The notion that it was only the most remote locations of rural Malaysia that would face problems was completely destroyed.

Taking this on board and, after much head-scratching, the government in November talked up digital or online learning in its annual budget. Key to this was Finance Minister Tengku Zafrul Tengku Abdul Aziz confidently announcing that 150,000 laptops would be made available to students from low-income families, in time for the start of the academic year in January 2021.

Six weeks into the new year and there is no sign of the laptops, or even the money to finance them. In its typical opaque manner, the government gives vague answers to queries when pressed hard enough but says nothing of substance.

Meanwhile, other critical flaws in the education system were prised open and not even the most optimistic of ministers could ever paint over the cracks.

Photo left: Malaysian student in class on July 8, 2020. (Photo by Azami Adiputera/shutterstock.com)

Aside from major public universities, Malaysia is also host to a variety of residential schools and colleges. In processing the events of 2020 and supposedly learning from any mistakes, the ministry required residential students to report to their respective college or school, where they would be taught face-to-face by the staff.

Yet, everything began to unravel quickly in true education ministry fashion.

Students were not required to take COVID-19 tests before they arrived, while, when teaching staff tried to implement social distancing procedures in the classroom, they were found to be completely unworkable.

Chaos ensued as students either fell sick or reported themselves as a close contact of a coronavirus case, creating a quarantining nightmare. After barely a few days of the term, teachers were sent home and told to teach online.

Then, there were unconfirmed reports that teachers had almost immediately been instructed to report back to work to invigilate exams for students supposed to be in strict isolation, and in breach of the Health Ministry’s protocol.

As officials scrambled to keep a lid on the issue, word got out that an entire college in the hills of central Malaysia had been quarantined. Moreover, students said they were effectively prisoners in their dormitories with food and water running short. Some also claimed they had been threatened by the college administration to keep quiet, allegations denied by an otherwise tight-lipped administration.

The case of students locked in on-campus brings the issue of connectivity back to the fore. Students regularly complain of problems with internet access while on-campus, making it difficult to follow lessons. Similarly, teachers complain students ‘drop off’ during class, ie the connection breaks.

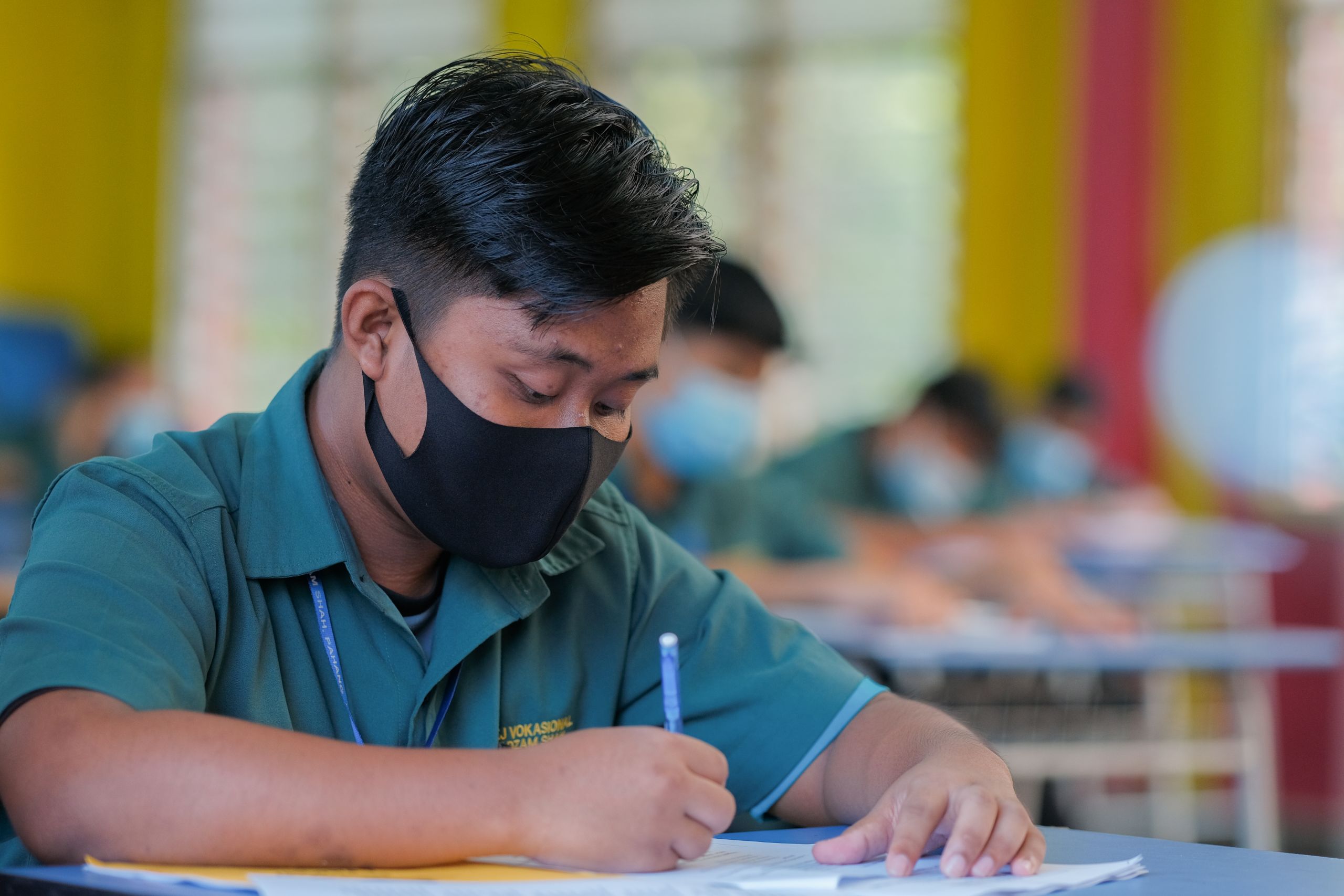

Photo left: Students wearing face masks during class in a Kuala Lumpur school on July 15, 2020. (By Naufal Zaquan/shutterstock.com)

It stands to reason. College internet systems are not the most advanced in the world, barely able to cope with occasional bursts of activity during evening peak hours when private study is required.

They are certainly not capable of hosting hundreds, or even thousands, of students collectively online for hours at a time, demanding broadband video or, at the very least, audio for lessons.

Parents are now understandably demanding the ministry allow their children to come home.

Students on the first day of their school reopening following restrictions to suppress the spread of the new coronavirus on June 24, 2020. (By Naufal Zaquan/shutterstock.com)

Students on the first day of their school reopening following restrictions to suppress the spread of the new coronavirus on June 24, 2020. (By Naufal Zaquan/shutterstock.com)

At the same time, parents of high school students due to sit major exams are bewildered by contradictory directives over whether their children need to start going to class.

These are just some of the issues that former education minister Dr Maszlee Malik says he receives, along with hundreds of complaints a day and asking for help.

He accuses his successor, Mohd Ridzi Md Jadin, of shirking his responsibilities and leaving his work to lackeys, who are doing a very poor job indeed.

Ridzi does not have much to say for himself, preferring to stone-wall the press.

A student wearing face mask at a primary school in Alor Setar Kedah, Malaysia on Sept. 9, 2020. (Photo by fuadstephan/shutterstock.com)

A student wearing face mask at a primary school in Alor Setar Kedah, Malaysia on Sept. 9, 2020. (Photo by fuadstephan/shutterstock.com)

Meanwhile, what few words that have come from the ministry bear a familiar monotone: everything humanly possible is being done to solve problems.

Now approaching one year into the job, the current government seems blissfully unaware that people are not impressed by this opaque rhetoric anymore, certainly when it is woefully mismanaging the country during a prolonged crisis.

People want transparency, to be heard and understood, not talked down to like a parent addresses a toddler.

Their children also have the right to be educated.

Yet, more than a year into this pandemic, this government that supposedly does everything for the people clearly has no idea how it will achieve this.

Gareth Corsi is a freelance journalist based in Malaysia. The views expressed in this article are the opinions of the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial stance of LiCAS.news.

Published February 12, 2021

© Copyright MMXXI LiCAS.news