Man who can’t speak gives voice to environment

Ramon Sta. Ana's words are slurred, but whatever voice is left of him, he uses to convince others to protect the environment.

Ramon Sta. Ana, also known as Mon, can barely speak after six successive strokes permanently damaged his speech motor. The 67-year-old former village leader in the Philippine province of Camarines Sur now depends on somebody else to interpret what he wants to say.

Mon’s words are slurred, but whatever voice is left of him, he uses to convince others to protect the environment. He is a “eucharistic minister” in his parish and an active member of the parish renewal experience.

His “love affair” with water and the environment started when he became village chief of Cagsao in the coastal town of Calabanga.

Although his term ended in 2013, people still remember his “love-hate” relationship with water, like when he fought for his village to have access to potable water and when he fought to defend the village from storm surges.

The village of Cagsao lies in the typhoon path of the Philippines’ Bicol region.

On sunny days, the sleepy town’s black sand beach is littered with seashells that reverberate like chimes when waves kiss the shore during low tide.

When high tide comes, however, the battering of the waves on the mountainside walls sounds like exploding canons.

The village is practically unheard of except when disasters hit and when its 10-hectare mangrove forest was planted in 2008.

In the morning, the towering trees and its gigantic roots are abuzz with fishermen and children in search of fish and shells. At night, it’s a sight to behold with the fireflies lighting the rural darkness.

If it weren’t for the trash that is carried by the tide, the site can be a perfect location for romantic movies.

“Everything is connected, and .. genuine care for our own lives and our relationships with nature are inseparable from fraternity, justice and faithfulness,” said Pope Francis in his encyclical “Laudato si’.”

During the pandemic, fishermen said they had no problem with food because of the good catch due to the mangroves. (Photo by Ciriaco Santiago III)

During the pandemic, fishermen said they had no problem with food because of the good catch due to the mangroves. (Photo by Ciriaco Santiago III)

Background photo: In 2007, villagers planted the mangroves with the aim of preventing storm surges to hit their community. (Photo by Ciriaco Santiago III)

The town that battles storms

The town of Calabanga is known for the disasters that hit it almost every year.

Located 405 kilometers south of Metro Manila, it sits on the path of typhoons that visit the country every year. Often, villages are brought to their knees by these disasters.

People in town know what climate change is all about with the storms that leave them homeless every year.

“What can be done?” Mon asked.

In 2007, he found out that a non-government group backed by the European Union was helping Calabanga’s three littoral villages — Punta Tarawal, Balatasan, and Balongay — reforest its shorelines with mangroves.

Cagsao villagers catch fish during low tide. (Photo by Ciriaco Santiago III)

Cagsao villagers catch fish during low tide. (Photo by Ciriaco Santiago III)

Like Cagsao, these villages are constantly affected by floods and storm surges.

Mon convinced the NGO to include his village in the project. How could they say no to a passionate man who seemed desperate to uplift the lives of his people?

The mangrove reforestation project was a community enterprise of the local government, the schools, and the Church in town.

Everything did not go well, however. People resisted the project, saying it was bound to fail like the projects in the past.

“Every year, we plant, but nothing happens,” said fisherman Jose Posada.

Mon, however, stood by what he believes is the solution to the problem his village is facing. The people’s cold reception of the project did not deter him. He launched an information campaign, saying that mangroves are their village’s best defense against storm surges.

He said Cagsao used to have a mangrove belt before people started cutting it, turning the shore into a wet desert and putting the village in the mercy of nature.

Erwin Guerrero, 8, joins the reforestation project in the village of Cagsao in 2008. (Photo by Ciriaco Santiago III)

Erwin Guerrero, 8, joins the reforestation project in the village of Cagsao in 2008. (Photo by Ciriaco Santiago III)

While campaigning for the project, Mon suffered his fourth stroke that further damaged his speech motor. The man was, however, unstoppable. He visited homes and convinced people about the benefits that the mangroves would offer.

Through interpreters, he explained how the mangrove forest can serve as a natural buffer against disasters and how it can also become a nursery to marine life.

Slowly, the people in his village and in his town were convinced. In April 2008, men, women, and children joined Mon in planting 150,000 propagules.

Background photo: A mother and a child collect seashells on the seashore. (Photo by Ciriaco Santiago III)

Ramon Sta. Ana, “caretaker” of the mangrove forest, says there is a need to reforest the mangroves to cover a wider area. (Photo by Ciriaco Santiago III)

Ramon Sta. Ana, “caretaker” of the mangrove forest, says there is a need to reforest the mangroves to cover a wider area. (Photo by Ciriaco Santiago III)

Seemingly endless battle

Mon’s battle to protect the mangroves continued. A group of fishermen asked for a “right of way” so that they could dock their boats. It would mean, however, cutting several young mangrove trees.

Mon said no and passed a village ordinance penalizing the cutting of mangroves.

During the 2013 village elections, Mon ran and lost.

Four years later, the Philippines’ Department of Environment and Natural Resources approved the cutting of young mangroves to pave the way for an “eco-tourism” site.

Background photo: Plastic and trash that are left by the tide hang on the mangroves. (Photo by Ciriaco Santiago III)

Several mangroves were cut to give way to a bamboo bridge and a hut in the middle of the plantation. It attracted tourists and visitors and turned the village of Cagsao into an online hit.

The forest attracted “vloggers” who talked about the mangroves’ beauty but not its destruction. Ironically, most vlogs called for the protection of the trees while the vloggers are standing on a mangrove plantation that has been destroyed.

Ramon Sta. Ana, mangrove forest “caretaker,” explains to visitors what happened to the 13-year-old forest. (Photo by Ciriaco Santiago III)

Ramon Sta. Ana, mangrove forest “caretaker,” explains to visitors what happened to the 13-year-old forest. (Photo by Ciriaco Santiago III)

The bridge fell after three years and the “eco-tourism site” was closed. The once “instagram-able” attraction has become trash in the heart of the forest.

Now, the villagers would not even dare cross the area where the bamboo bridge used to stand. It was built using iron nails that are now embedded in mud.

Mon said the “eco-tourism project” came too soon. “The mangroves are meant to protect the village from surges, not a tourist attraction,” he said through interpreter Armando Torres.

Mon never made a comeback in politics, but he continued to watch over the forest as a caretaker. The former village chief has no qualms picking up garbage that hangs on the mangroves.

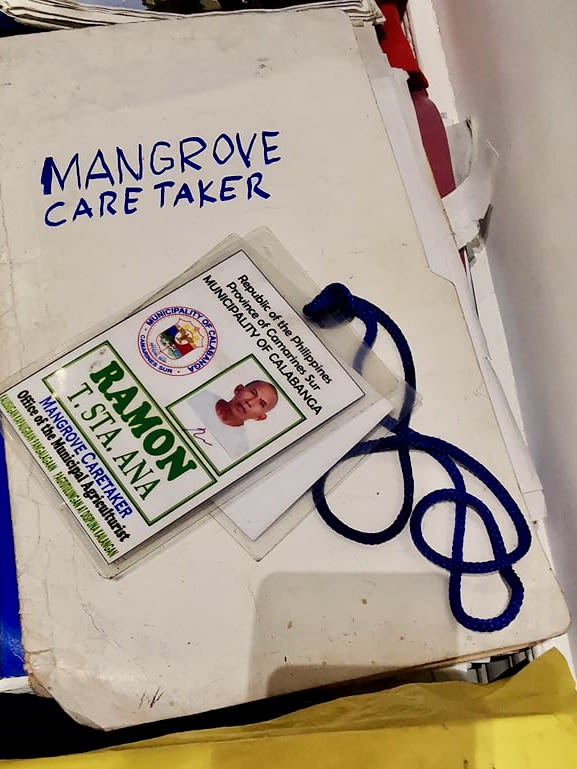

Ramon Sta. Ana, former village chief, identifies himself as the “caretaker” of the forest with his identification card. (Photo by Ciriaco Santiago III)

Ramon Sta. Ana, former village chief, identifies himself as the “caretaker” of the forest with his identification card. (Photo by Ciriaco Santiago III)

Mon has always loved the sea, even when he was a young man, but his father, a fisherman, did not want his son to end up like him. The father sent Mon to Manila for a university degree, but after graduation he came back to the village “to serve nature.”

In 2020, before the pandemic, village officials passed a resolution calling for the demolition of a mound that sprouted near the seashore because it was blocking the fishermen’s way to the sea.

Mon opposed the proposal. The piece of land that the fishermen wanted removed turned out to be a moor, a natural sea wall that came out of the mangroves.

Today, the villagers are saying that the fishermen are having a good catch. There were no more storm surges. The mangrove forest has become an “outdoor classroom” for students and environmentalists who want to study nature.

The local government now prides itself as a “protector of the environment.” The international NGO is congratulating itself for a “job well done.”

Mon remains silent. Caring for the forest is his legacy to his village. It was his contribution to the rebuilding of the “common home.”

Brother Ciriaco Santiago III is a religious missionary of the Congregation of the Most Holy Redeemer, commonly known as the Redemptorists. The research and writing of this story was made possible through the support of Internews’ Earth Journalism Network and the Photojournalists’ Center of the Philippines.

Text and photos by

Brother Ciriaco Santiago III, CSsR

Published November 30, 2021

© Copyright MMXXI LiCAS.news

Ramon Sta. Ana stands near the natural seawall that grew out of the mangrove forest. (Photo by Ciriaco Santiago III)

Ramon Sta. Ana stands near the natural seawall that grew out of the mangrove forest. (Photo by Ciriaco Santiago III)