Media: The other COVID-19 frontliners

Most affected by the pandemic are the freelancers, especially provincial reporters and photographers who are paid for every story or photograph used

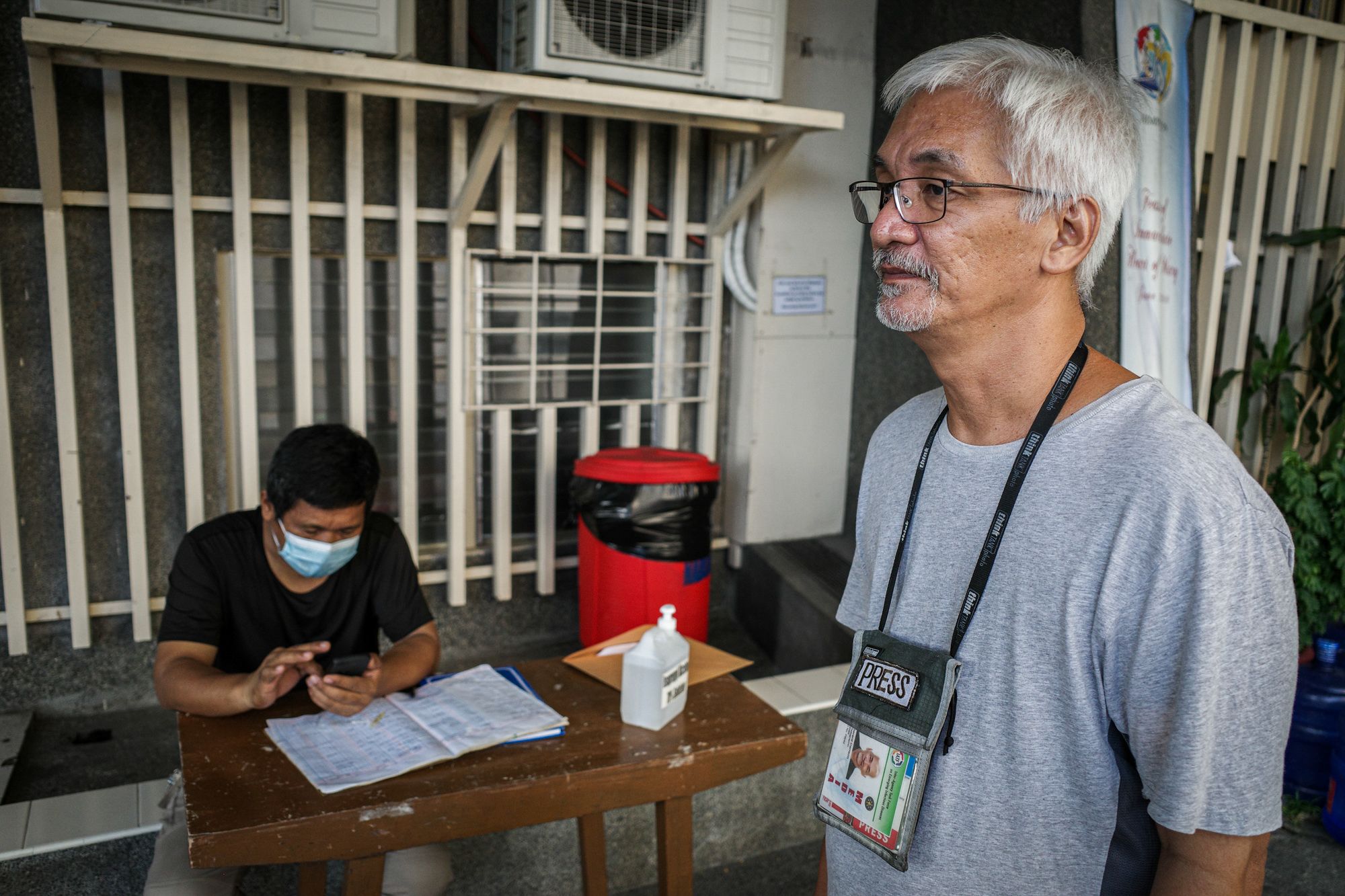

For over a month now, photojournalist Gerard Carreon has been wearing the smell of ethyl alcohol that irritates his nose.

But it's the only way for him to stay clean and disinfected when he goes out for work and has no chance to wash with soap and water.

Carreon, Jire to his friends, said he already lost track how many bottles of disinfectant he has used.

He knows that spraying and rubbing alcohol is not enough protection from the new coronavirus disease.

Gerard Carreon has been covering the impact of the pandemic for over a month already. (Photo by Mark Saludes)

Gerard Carreon has been covering the impact of the pandemic for over a month already. (Photo by Mark Saludes)

Jire, who shoots for LiCAS.news, and two other photojournalists — Maria Tan and Angie de Silva — had to seek temporary sanctuary in a church basement after several people tested positive of COVID-19 near their press corps office.

"I had to impose some restrictions on myself," said Jire who has been covering the Philippine capital since pandemic broke.

Photojournalists Gerard Carreon, Maria Tan, and Angie de Silva seek temporary sanctuary in the basement of a parish church in Quezon City. (Photo by Mark Saludes)

Photojournalists Gerard Carreon, Maria Tan, and Angie de Silva seek temporary sanctuary in the basement of a parish church in Quezon City. (Photo by Mark Saludes)

"I am out every day, but I only go to places where I do not have to put on a hazmat," he said. "I only choose places where there is low-risk of community transmission," added Jire.

"You know there’s a threat but you can’t see it," he said, adding that "now is not the right time to be careless."

Photojournalist Angelo de Silva cooks food in the basement of a church in Manila where he and his colleague sought shelter. (Photo by Mark Saludes)

Photojournalist Angelo de Silva cooks food in the basement of a church in Manila where he and his colleague sought shelter. (Photo by Mark Saludes)

Every time he goes out to shoot, the 56-year-old photojournalist makes sure to have his personal protection equipment, or PPE, on hand.

"I just hope that I will not have to wear those PPEs," said Jire whose work focuses on the impact of the lockdown on various sectors.

Maria Tan helps Gerard Carreon into a hazmat suit before going into a coverage. (Photo by Mark Saludes)

Maria Tan helps Gerard Carreon into a hazmat suit before going into a coverage. (Photo by Mark Saludes)

Whole new situation

The pandemic is a whole new situation for journalists and media workers, changing their daily routines.

Sara Gomez Armas, Manila correspondent for the Spanish news agency EFE, noted that phone interviews and video press conferences have become the "new normal for the profession."

Sara, who is president of the Foreign Correspondents Association of the Philippines, said the challenge is much bigger for visual journalists who have to do face-to-face interviews.

"They have to deal with new technical issues," she said, adding that keeping "social distance" while taking photos or video is difficult.

A police officer stands guard as photojournalist Jun Sepe takes pictures during the implementation of the "enhanced community quarantine" in Manila. (Photo by Basilio Sepe)

A police officer stands guard as photojournalist Jun Sepe takes pictures during the implementation of the "enhanced community quarantine" in Manila. (Photo by Basilio Sepe)

Another challenge is getting reliable data on the situation because information has been changing almost every minute.

"As long as they keep studying the coronavirus disease, data change," she said.

The Philippine government has given media practitioners in the country exemption from the lockdown to allow them to continue their "essential service" to the public.

Angie de Silva and Gerard Carreon takes time to watch television while not taking pictures outside during the lockdown. (Photo by Mark Saludes)

Angie de Silva and Gerard Carreon takes time to watch television while not taking pictures outside during the lockdown. (Photo by Mark Saludes)

Media companies and organization have implemented their own protocols, including restrictions on places to cover such as hospitals and crowded areas.

Many journalists have managed to continue with their reporting using teleconferencing mobile and online apps.

But there are those who must go out to take those photos.

In the central Philippine province of Cebu, award-winning photographer Victor Kintanar said the lockdown has affected his income.

"There were two workshops that I had to drop," he said, adding that he is worried if he can conduct workshops even after the quarantine period is over.

Unlike journalists in the capital, Victor has a hard time acquiring protective gear due to the scarcity of supply in the provinces.

He said he is worried to go and do some reporting because "I am worried about the stigma and what my neighbors might think."

He said if he goes out without wearing the proper PPE people in the neighborhood would suspect him of bringing the virus from outside.

Varying interpretations of lockdown protocols by local authorities also hinder journalists from doing their job.

"People at checkpoints have different interpretations of the rules," said Victor.

Some journalists have formed a Facebook Group to serve as venue for discussions on how to cover the frontlines of the pandemic.

The social media page has also become a forum for journalists to exchange contacts who can help provide PPEs and other equipment.

"We need everyone to share their thoughts about this crisis because we are in an extraordinary time," said New York Times contributing photographer Jes Aznar.

Jes said journalists must be reminded that "we cannot do what we normally do in the past" even with all the safety gear.

The Photojournalists’ Center of the Philippines has also initiated the distribution of PPEs for members.

"While we encourage everyone to pursue stories related to COVID-19, we would not encourage anyone to take risks, just as we would not tell anyone just to stay home," said Fernando Sepe Jr., chairman of the organization.

"It is our belief that the decision to cover, and that includes what length one wants to go, is the personal decision of each individual," said Sepe.

"What we can only give are reminders on safety and proper precautions if they choose to stay inside or venture out," he added.

Photojournalists take photos of a workers disinfecting the streets of the Philippine capital. (Photo by Basilio Sepe)

Photojournalists take photos of a workers disinfecting the streets of the Philippine capital. (Photo by Basilio Sepe)

Media business affected

The pandemic has mostly affected the print industry in the Philippines.

The tabloid Remate, which has a daily general circulation of about 430,000 copies, was one of the first media outfits to temporarily close its print operations due to lockdown.

Lydia Bendaña Bueno, the paper’s editor-in-chief, said its 30 regular employees and more than 200 contributors and contractors across the country have been affected.

"We were able to pay the salaries of the regular staff in the first one and a half months, but we are still working it out for the next payday," she said.

Lydia Bendaña Bueno, Remate’s editor-in-chief, says at least 30 regular employees and more than 200 contributors and contractors of the tabloid have been displaced by the pandemic. (Photo by Mark Saludes)

Lydia Bendaña Bueno, Remate’s editor-in-chief, says at least 30 regular employees and more than 200 contributors and contractors of the tabloid have been displaced by the pandemic. (Photo by Mark Saludes)

Bueno said the most affected workers are the freelancers, especially the reporters and photographers in the provinces who are paid for every story or photograph used.

On a normal day, Remate’s main office is one of the busiest offices in the Intramuros district of Manila with more than 50 working journalists coming in and out every day.

Today, only a few people are left to maintain the office. Computers are shut off, cubicles are empty, and silence is all over the place.

The office of Remate in Manila is empty after the tabloid temporarily suspended its print operations. (Photo by Mark Saludes)

The office of Remate in Manila is empty after the tabloid temporarily suspended its print operations. (Photo by Mark Saludes)

Although some of the reporters, writers, photographers, and layout artists have been "absorbed" in the paper’s online operation, Bueno said there is still no guarantee of getting published.

"Those who were working for the paper can submit their articles and photos in the online publication, but as much as we want to, we cannot publish every one of them," she said.

The paper decided to temporarily stop it print operations due to the lack of advertisements and the hampered distribution line.

Remate is dependent on third-party distributors that manage the sale and circulation of the paper across the country.

Photojournalist Maria Tan prepares her gear before another day of covering the pandemic in the Philippine capital. (Photo by Mark Saludes)

Photojournalist Maria Tan prepares her gear before another day of covering the pandemic in the Philippine capital. (Photo by Mark Saludes)

Photojournalists take time to relax in the middle of a coverage. (Photo by Mark Saludes)

Photojournalists take time to relax in the middle of a coverage. (Photo by Mark Saludes)

Volunteers pack relief goods for distribution to media workers at the National Press Club of the Philippines. (Photo by Mark Saludes)

Volunteers pack relief goods for distribution to media workers at the National Press Club of the Philippines. (Photo by Mark Saludes)

Paul Gutierrez, vice president of the National Press Club of the Philippines, said the lockdown "has damaged industries including news publications."

The media organization has received reports that many community newspapers have closed down for failure to cope with the situation.

Small publications will definitely suffer, said Gutierrez.

"They do not have the resources that can last for months," he said.

"What concerns us the most is not the possibility of contracting the virus but the threat of losing our jobs," he said.

© Copyright MMXX LiCAS.news

Photojournalists Angie de Silva, Maria Tan, and Gerard Carreon prepare to take their first meal of the day. (Photo by Mark Saludes)

Photojournalists Angie de Silva, Maria Tan, and Gerard Carreon prepare to take their first meal of the day. (Photo by Mark Saludes)