Migrant workforce woes bite Malaysia hard during crisis

Govt discovering its neglect of foreign labour is now exacting a heavy toll

It seems rather ironic that, approaching one year ago, Malaysia was viewed with such high international regard as it was notably successful in controlling the coronavirus pandemic.

While the US and countries in Western Europe were ravaged by COVID-19, and their respective health services began to creak and groan under the pressure, Malaysians were mercifully spared.

Strict, bordering on paranoid, movement controls meant that the number of new daily cases barely registered in double digits.

Yet, five months later, everything unravelled. Carefully constructed plans and protocols laid out by Director-General of Health Dr Noor Hisham Abdullah were tossed out of the window for political gain.

The eastern state of Sabah suffered terribly as a snap election allowed the virus to spread like wildfire. Consequently, the virus spread nationwide as electoral campaigners and politicians then returned to the peninsula to infect those around them.

Adding insult to injury, over the past few months, Malaysia’s sore underbelly has once again been exposed:

Its migrant workforce.

A government health worker searches for foreign migrant workers for COVID-19 screening testing in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia on May 16, 2020. (Photo by Abdul Razak Latif / shutterstock.com)

A government health worker searches for foreign migrant workers for COVID-19 screening testing in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia on May 16, 2020. (Photo by Abdul Razak Latif / shutterstock.com)

Background photo: Foreign workers wait in line to be tested for COVID-19 outside a clinic in Kajang, Malaysia on Oct. 26, 2020. (Photo by Lim Huey Teng/Reuters)

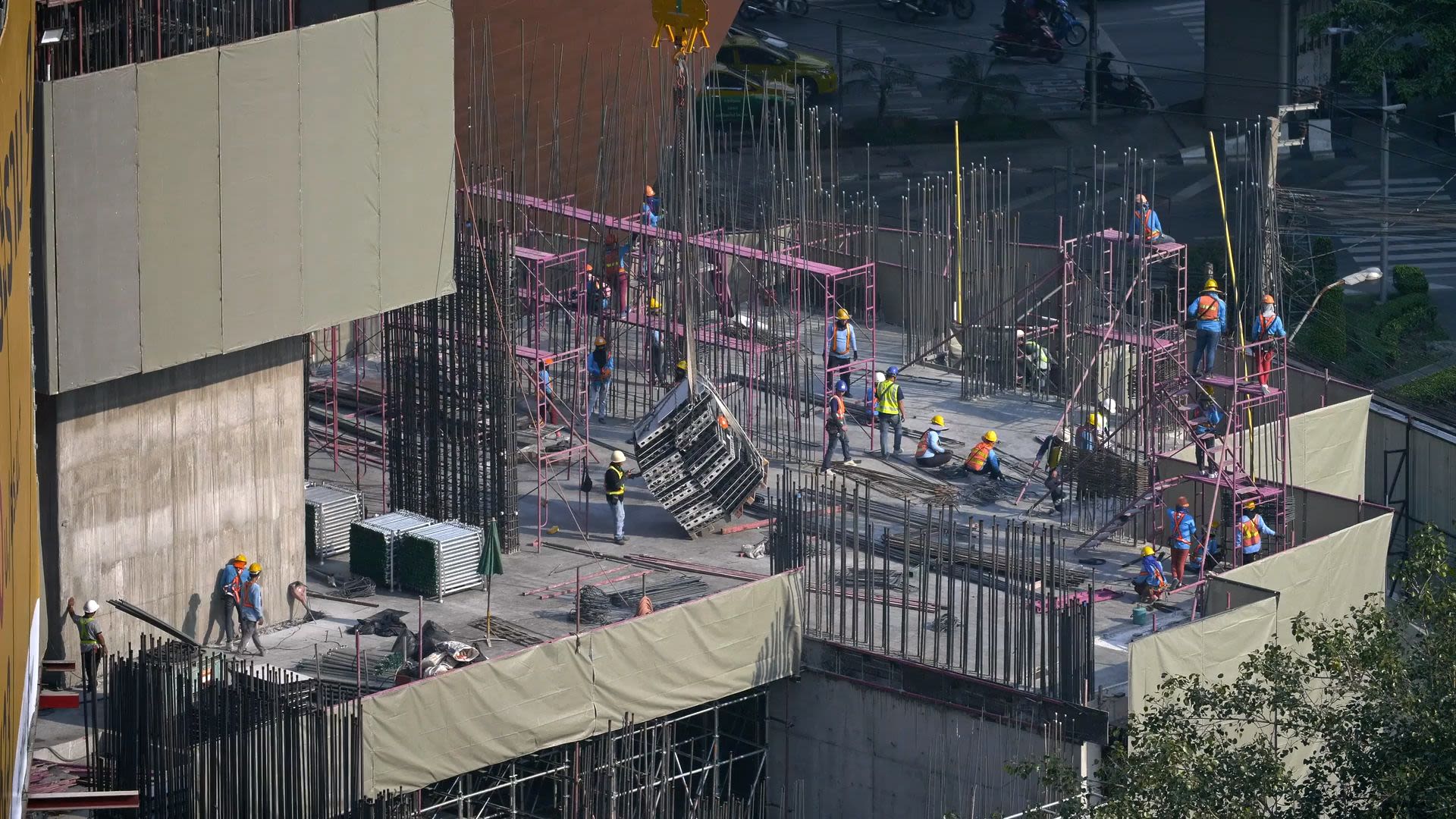

The nation employs roughly 2 million migrant workers, performing an array of semi-skilled and unskilled tasks to keep the country ticking over, from sweeping the streets to factory work, to tilling the fields.

Note that these are the people legally registered to work. Independent analysis points to anywhere between a further 2 million and 4 million undocumented migrants. The government would have you believe that these people are all hardened criminals, dodging border patrols to take advantage of cash jobs in Malaysia.

The reality is that most workers are brought in legally, then duped by unscrupulous agents or employers into some other form of employment in violation of their work permit. For example, men brought in for what they think is a relatively cushy construction job in Kuala Lumpur may end up on a farm in the Cameron Highlands 150km away.

The problem is systemic in that the country has relied on migrant labour for decades, with ordinary Malaysians not knowing or even caring about the issue until it hits the headlines.

Which it did. Late last year, an outbreak at Top Glove, a global leader in rubber glove production and one of Malaysia’s shining corporate stars, came to international attention.

A British documentary team exposed the general working conditions in the factories, staffed by upwards of 10,000 people, while highlighting the cramped and — according to the production team — squalid conditions in which workers were expected to live.

When the authorities arrived to investigate, they did cite Top Glove for numerous health code violations regarding living conditions, but it could be argued that their dormitories were positively palatial compared to some at other companies.

Background photo: A worker inspects newly-made gloves at Top Glove factory in Shah Alam, Malaysia Aug. 26, 2020. (Photo by Lim Huey Teng/Reuters)

Having largely ignored migrant workers during the outbreak, the Top Glove incident prompted the authorities to carry out more intense screening.

So, officials started going door-to-door, visiting companies across the country’s major industrial centres in the Klang Valley, Johor and Penang.

They probably wished they had stayed at home. An untold number of migrant workers do not reside in brick-and-mortar accommodation, spending their nights in cargo containers, which can house anywhere between five and 25 people, depending on the employer.

While some enterprising workers have made their living space barely habitable, cutting windows into the sides of their metal box and supplying a smattering of creature comforts, many have no such so-called luxury. And this is for workers who are living in Malaysia legally.

No running water, no sanitation and certainly no electricity. Paradise for a pathogen like COVID-19.

This is exactly what healthcare workers found as they opened one container after another, the virus had spread like the very thing it is — a plague.

Background photo: Government health worker does a COVID-19 test to a foreign migrant worker in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia on May 15, 2020. (Photo by Abdul Razak Latif/shutterstock.com)

Meanwhile, Noor Hisham has become a household name in no small part due to his kind demeanour as he delivers his daily televised address, keeping the nation informed on the day’s events. He has been a reassuring sight for many people, trying to offer some clarity during very difficult times.

Yet, in recent weeks, you would have seen the marked change in him. Once scared by new cases just topping the 100-mark, he broke into a sweat when it became 500, then alarm when it soared through 1,500 cases.

By the time Malaysia’s daily caseload breached 6,000, you can imagine the poor man must have been close to stroking out.

The strain on the health service has been equally telling with conference centres, education facilities, army camps, disused prisons and even a former leper colony turned into makeshift quarantine zones.

It has been a few weeks since that day and numbers have halved since then, but it has not been a steady downward trend. Periodically, numbers spike by several hundred as health workers arrive at another factory and fling open the doors to another dose of coronavirus reality.

Remember, this is just the legal workers. The implications for tying in undocumented migrants to the equation are impossible to calculate because there is almost no data. The government keeps scant records of a huge segment of society it denies even exists.

This adds to an already intense situation: Seven weeks ago, Prime Minister Muhyiddin Yassin declared a state of emergency — which was ostensibly to control the pandemic but was more likely aimed at clinging on to power — making him in effect a dictator.

Malaysia Prime Minister Muhyiddin Yassin during a press conference on March 26. (Photo by OS/shutterstuck.com)

Malaysia Prime Minister Muhyiddin Yassin during a press conference on March 26. (Photo by OS/shutterstuck.com)

However, despite promising to return full democratic norms by August at the latest, Muhyiddin is already facing an increasingly restless lockdown-weary population growing more impatient by the day, coupled with angry parliamentarians, insistent that he reopen the debating chamber at once — a call echoed by the king recently.

While the king is a constitutional figurehead and has no direct political influence, it is considered to be offensive at best, bordering on sedition at worst to ignore him.

Even the hope of a vaccination rollout is doing little to ease fears among Malaysia’s undocumented population. Science, Technology and Industry Minister Khairy Jamaluddin has repeatedly tried to reassure undocumented migrants that they need to step forward and be inoculated, there will be no repercussions.

However, migrants have heard these promises before. Defence Minister Ismail Sabri Yaakob made gave similar reassurances in April last year before ordering thousands of migrants to be rounded up and deported in a chilling betrayal that made global headlines.

Many migrants are already telling aid workers and charities they would rather take their chances with the virus than step into the light.

So, while the current situation may not be of Muhyiddin’s making, he cannot deny his role in how migrant workers are suffering. He has been at the highest level of government for 25 years, a government that has perennially tried to sweep migrant worker issues under the carpet.

Now these issues are coming back to bite — and bite hard.

Gareth Corsi is a freelance journalist based in Malaysia. The views expressed in this article are the opinions of the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial stance of LiCAS.news

Published March 2, 2021

© Copyright MMXXI LiCAS.news