No place like home

Wondering the streets and addicted to drugs, homeless children in Bangladesh finds a home in 'Khichuri'

Mahfuz was just seven years old when he left home and started wandering the streets.

At a very young age, his parents sold him to another couple, by whom he was abused. He also suffered abuse from his teachers at the Madrasa (Islamic education center) where he was sent to study. Outside the school, he was labeled as “adopted,” with no parents to protect him.

Mahfuz had no place to call “home".

After leaving home in 2012, life became even more difficult for Mahfuz. He began asking people for food, collecting and selling plastics found on the streets, and occasionally buying food with the money he earned by carrying goods for people at railway stations and launch terminals.

Mahfuz had to sleep on roadsides, at railway stations, or launch terminals. During this time, he encountered many young children addicted to various substances, including alcohol, marijuana, heroin, phensedyl syrup, and yaba (tablets containing a mixture of caffeine and methamphetamine, produced in Myanmar).

Grim streets

In December 2023, the Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics, with support from UNICEF, published the 'Survey on Street Children 2022'. While the total number of street children wasn't specified, UNICEF experts estimate it could exceed one million.

The survey revealed a grim reality: 79 percent of street children have suffered mental, physical, or sexual abuse. A lack of parental identification subjects 76 percent to emotional abuse, harassment, and derogatory language. Additionally, 62 percent have endured physical abuse.

On average, a street child begs for 10 hours a day. Economic hardship drives 37.8 percent of these children to the streets, while 15.4 percent follow their parents to urban areas, and 12.1 percent seek employment, often arriving in the city alone. Remarkably, two out of every five street children come to the city by themselves.

Gradually, Mahfuz too fell into the grip of addiction. However, his life took a significant turn when he encountered a church-run rehabilitation center.

"One day, I discovered a drop-in center operated by BARACA (Bangladesh Assistance and Rehabilitation Center for Addicts), where I was allowed to have khichuri for lunch for free," he said. (Khichuri is a Bangladeshi dish made of rice, lentils, and vegetables.)

After two years of wandering the streets, Mahfuz has been able to secure at least one meal a day at BARACA since 2014. In 2016, BARACA extended their support by providing overnight accommodation at their drop-in center, and Mahfuz began staying there.

Like Mahfuz, about 50 other children under the age of 18 began residing at the center. In 2017, BARACA initiated an educational program at the school Mahfuz attended, starting with just three students enrolled.

This year, Mahfuz is set to take the secondary examination from a UCEP (Underprivileged Children's Educational Programmes) school. Established in 1972, UCEP Bangladesh is a non-government organization provides "Second Chance Education" to out-of-school children.

Simultaneously, he completed a three-month electrical course at a technical education institution operated by Caritas Bangladesh. Meanwhile, Mahfuz has found employment as a cook at another drop-in center, earning a salary of 8000 taka (around US$70) per month.

“Drug addiction is completely gone from my life. I am now studying and even managing to save some money every month from my income.”

Children ranging from very young to 18 years can stay in the drop-in center.

Children ranging from very young to 18 years can stay in the drop-in center.

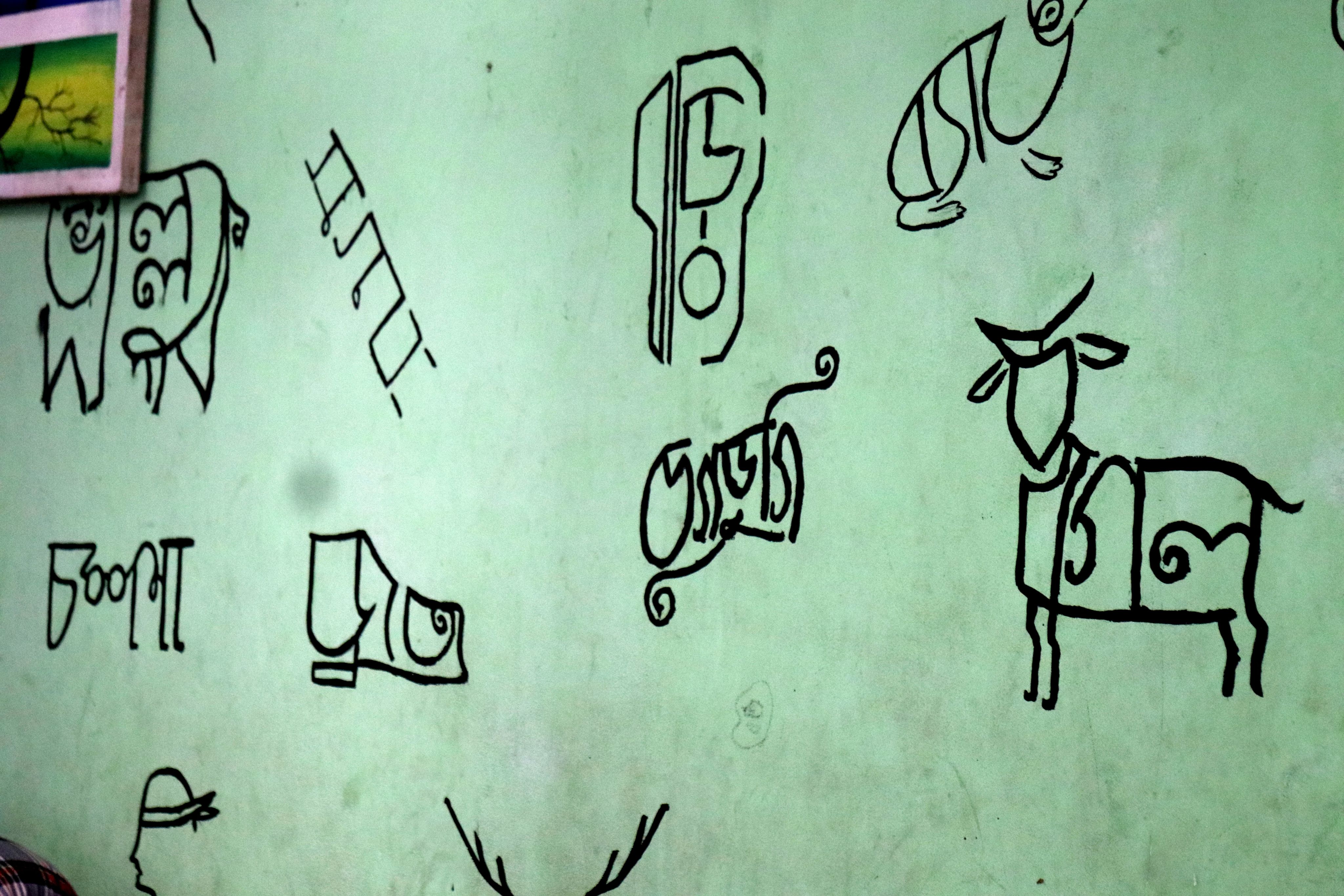

Children staying in the center paint on the wall.

Children staying in the center paint on the wall.

Street children who are living in a drop-in center run by BARACA, having lunch.

Street children who are living in a drop-in center run by BARACA, having lunch.

The children are gaining technical work experience from APON.

The children are gaining technical work experience from APON.

Children sleeping on the floor at the drop-in center run by BARACA.

Children sleeping on the floor at the drop-in center run by BARACA.

Center of hope for lost souls

BARACA is a non-governmental, non-profit volunteer development organization that stands as the inaugural drug treatment and rehabilitation center in Bangladesh. Initiated by the Holy Cross Brothers and serving as a central project of Caritas Bangladesh, it began its operations on July 1, 1988.

The organization is dedicated to offering a range of services, including treatment and rehabilitation for drug-dependent individuals (both male and female), awareness campaigns about drugs, harm and risk reduction strategies, Voluntary Counseling and Testing (VCT) for drug-dependent persons, and providing day-care and night shelter facilities for street-based children at risk.

According to BARACA's director, Holy Cross Brother Francis Nirmal Gomes, the initiative to establish institutions like BARACA came from the Holy Cross Brothers' observations of inattentive students at their school, who were found to be drug addicts. This discovery prompted them to consider treating drug addiction, leading to the creation of BARACA.

Brother Gomes recounted how, in pursuit of solutions for drug addiction, the Holy Cross Brothers engaged with local communities, leading to Brother Ronald Drahozal being tasked with spearheading this initiative. Under his leadership, BARACA was founded in 1988. Brother Drahozal managed BARACA until 1995, when it became a specialized project under the Catholic charity Caritas Bangladesh.

During his tenure, Brother Drahozal, together with Brother Donald J. Becker, also established APON (Ashokti Punorbashon Nibash), an addiction rehabilitation residence, in Muhammadpur in 1994, thanks to contributions from his family and relatives. APON relocated to Manikganj in 2007, supported by both local and international donors.

Today, both BARACA and APON are operated by the Holy Cross Brothers, continuing their mission to combat drug addiction in Bangladesh. While APON functions independently with its own curriculum and administrative policies, BARACA operates under the guidelines set by Caritas.

Challenges: Then and Now

"Starting BARACA was fraught with challenges," Brother Gomes reflected. "Initially, our efforts weren't recognized by the government, which posed a significant hurdle.”

Financial constraints and a lack of experience in drug rehabilitation added to the difficulties. To overcome this, Brother Ronald and the newly recruited staff traveled to various countries to receive training at established drug addiction rehabilitation centers.

Today, Bangladesh is home to 370 private rehab centers, with 90 percent of them managed by individuals who were rehabilitated through APON and BARACA. Their success is a testament to the effective training and knowledge acquired from our programs, according to the religious brother.

BARACA now operates four drop-in centers, offering day and night accommodation for about 100 individuals and day-only services for an additional 50.

The main center is equipped to treat over 50 people at a time. Both BARACA and APON emphasize outreach efforts, particularly in regions known to be origins for many addicts and street children.

Our outreach workers engage directly with these individuals, offering conversation, motivation, and sustenance. Those who are willing are initially brought to our drop-in centers and, if they agree, eventually to our main treatment facility,” said Brother Gomes.

Brother Gomes pointed out a significant challenge in drug rehabilitation: some drugs on the market severely damage the brain, making recovery difficult. Compounding the issue is the lack of specialized education in drug addiction rehabilitation and addiction psychology within the country.

“We've initiated discussions with universities to introduce at least one course on the psychology of drug addiction, where our staff could contribute as instructors. They have been receptive to this idea,” Brother Gomes shared.

Despite the availability of rehabilitation services, seeking help from a rehab mentor is not common in Bangladeshi society. Stigma persists even after recovery, with families and even spouses often doubting the individual's return to normalcy.

Brother Gomes lamented the societal barriers to effective rehabilitation, emphasizing the critical need for social and family emotional support.

“Our society still clings to social taboos. I want to convey that drug addicts are not insane; they are unwell. With the right treatment, they can fully recover and reintegrate into society, but achieving this requires support at every level,” he asserted.

Government efforts

The Ministry of Social Welfare, through the Department of Social Services, is undertaking initiatives to support underprivileged children, including the Child Sensitive Social Protection in Bangladesh project and Services for the Children at Risk.

Government reports from January 2012 to February 2015 indicated that 14,884 street children received social protection services via Drop-in Centers, 758 were reunited with their families, 5,229 were given access to Emergency Night Shelter, 4,578 to Child-Friendly Space, and 23,617 to Open Air School.

Despite these efforts, the government's 70 child houses, each with a capacity for at least 100 residents, face criticism. Key issues include poor management, inadequate care from staff, and a lack of drug rehabilitation services for addicted children.

Abdul Jabbar, an assistant director of the social services department, asserted that these homes provide safe shelter, food, and education. While acknowledging the absence of targeted interventions for drug addiction, Jabbar suggested that improving overall living conditions for these children might also address the drug issue indirectly

Association for the Rights of Children in Southeast Asia (ARCSEA) holds a session on laws protecting children as part of the series of discussions that they hold in communities and schools.

Association for the Rights of Children in Southeast Asia (ARCSEA) holds a session on laws protecting children as part of the series of discussions that they hold in communities and schools.

In late 2012, Mahfuz, at just 7 years old, left home with a sense of uncertainty; now he is 16 and has a job through BARACA.

In late 2012, Mahfuz, at just 7 years old, left home with a sense of uncertainty; now he is 16 and has a job through BARACA.

Holy Cross Brother Francis Nirmal Gomes, the running director of BARACA and former director of APON.

Holy Cross Brother Francis Nirmal Gomes, the running director of BARACA and former director of APON.

Widening reach, ending drug addiction

Approximately 5,500 individuals have benefited from BARACA, and about 6,500 from APON. Brother Gomes, speaking to LiCAS.News, likened the recovery of individuals from addiction through APON and BARACA to a resurrection.

He emphasized the necessity of trained professionals in social development as a top priority and committed to continuing these services until the Bangladesh government is able to assume full responsibility.

BARACA and APON aspire to create a drug-free Bangladesh in collaboration with all rehabilitation centers in the country.

To this end, they have established The Rehab Centers of Bangladesh, an organization where all national rehab centers are members. Notably, the director of BARACA is positioned as the head of this umbrella organization.

Brother Gomes identified financial resources and training as the two primary needs for this initiative. He is currently in talks with donors to support these needs, aiming to foster trust in all centers and ensure safe treatment for drug addicts.

He stressed the importance of holistic development across all centers to prevent any from lagging behind, ensuring no disparity in the quality of rehabilitation services.

“We want people to be able to trust all the centers and treat drug addicts safely there,” he said.

With generous support from

Aid to the Church in Need

Dreikönigsaktion

missio Aachen

Text and photos by Stephan Uttom Rozario

Edited by Mark Saludes

Produced by June Nattha Nuchsuwan

Published March 8, 2024

© Copyright MMXXIV LiCAS.news