Pandemic, ‘development project’ threaten survival of Philippine tribe

Many times people are tagged as criminals when they resist development projects, says Aeta man

Danilo lives in a hut on top of a hill in a hamlet known to locals as Alli in the hinterlands of the town of Capas in the province of Tarlac, north of the Philippine capital Manila.

Every year in the past, he would make it a point to visit his friends in the neighboring province of Zambales. He would start his journey about three o’clock in the morning and reach his destination before midnight.

The crisp mountain air and the canopy of trees would make his day-long walk under the sun bearable. Even without a map, Danilo knows the rivers to cross and the mountains to trudge.

An Aeta, a collective term for several Filipino indigenous peoples who live in various parts of the island of Luzon, Danilo would smile when he hears townsfolk complain about long walks.

Danilo's shelter in Sitio Alli, Capas town, Tarlac, is made of bamboo, cogon grass, and tarpaulins. Living close to a road construction site, he and his wife sometimes could not sleep because of the noise at the construction site. (Photo by Bernice Beltran)

Danilo's shelter in Sitio Alli, Capas town, Tarlac, is made of bamboo, cogon grass, and tarpaulins. Living close to a road construction site, he and his wife sometimes could not sleep because of the noise at the construction site. (Photo by Bernice Beltran)

It has been three years, however, since Danilo was able to visit his friends in Zambales. It’s already too hot to walk the mountains, he said.

The trees that once shielded him from the sun have been uprooted by the government to give way to the establishment of New Clark City.

The project under the government’s “Build! Build! Build!” infrastructure program aims to convert 9,450 hectares of mountains, hills, and plains into a “smart green city.”

The city promises to utilize “greener energy resources” to power utilities. It also aims to attract investors who can set up businesses and create jobs for people in the region.

But for indigenous peoples like Danilo, this kind of “development” is “bad news.”

Danilo stands on the ground where he burned wood and excavated soil to make charcoal. Without his farm, he struggled to make ends meet. (Photo by Bernice Beltran)

Danilo stands on the ground where he burned wood and excavated soil to make charcoal. Without his farm, he struggled to make ends meet. (Photo by Bernice Beltran)

A golf course is now being constructed on his four-hectare farm, which used to be his only source of income.

The project will reportedly displace about 20,000 indigenous peoples, including Danilo.

An inquiry in the Philippine Senate has been assured by the project proponents that ancestral lands will not be affected.

Opposition Senator Risa Hontiveros, however, noted that “it obscures the difficulties” the Aetas experience in securing land titles.

A Senate report noted that the indigenous people have submitted the requirements to obtain land titles in 1999, in 2014, and again in 2019. They never succeeded.

Senator Hontiveros said “the mindset of the general public, including the government, is that the [indigenous peoples] are indebted to the government.”

A concrete marker in Binyayan, a farming village, in Capas, Tarlac. Residents said they were told to leave the place to give way to the construction of the new city in 2021. (Photo by Bernice Beltran)

A concrete marker in Binyayan, a farming village, in Capas, Tarlac. Residents said they were told to leave the place to give way to the construction of the new city in 2021. (Photo by Bernice Beltran)

For centuries, the Aetas lived in harmony with nature before they shifted to farming. Danilo’s ancestors hunted and gathered food in the forest.

Indigenous people’s lands cover about 20 percent of the planet’s surface, according to the United Nations. This comprises 80 percent of the global biodiversity.

Strong allies against climate change

Dave de Vera of the Philippine Association for Intercultural Development had mapped out ancestral lands and key biodiversity areas across the Philippines.

His maps show that places with rich biodiversity are mostly located within ancestral lands.

De Vera said the indigenous peoples are “our strongest allies against climate change.” Unfortunately, they have become among the most vulnerable to the effects of climate change.

Prolonged droughts and rainy seasons mess up cropping cycles, resulting in loss of livelihood for many tribes.

After losing his farm to the government’s development project three years ago, Danilo built a temporary shelter, hoping that one day the government would pay for his land.

“I planned to use that money to buy a house in another town,” he said.

To this day, he has not received a single centavo nor heard anything about the promised payment.

“If I only knew what would happen to my land, I would have not consented to the project,” he said.

He claimed that no one told him about the construction project.

De Vera said that it has become “common” in the Philippines that developers would claim that they secured the people’s consent to a project even if no consultation was done.

Many times people are “subjugated” or tagged as “criminals” when they resist “development projects,” he said.

“Worse, they are given positions in the government as a ‘token’ to add ‘diversity’ to (propaganda) photos,” said De Vera.

Projects are often imposed by “experts” who would dismiss traditional practices that are “not aligned with scientific methods.”

Dr. Theresa Mundita Lim, executive director of the ASEAN Centre for Biodiversity, said the massive loss of biodiversity in the country threatens to reduce “our capacity to become resilient.”

Studies show that environmental changes and unsustainable agricultural practices have led to the emergence of zoonotic diseases, such as COVID-19.

Days have become intensely hot and the nights are cold in Sitio Alli, a hill in the outback of Capas in Tarlac. (Photo by Bernice Beltran)

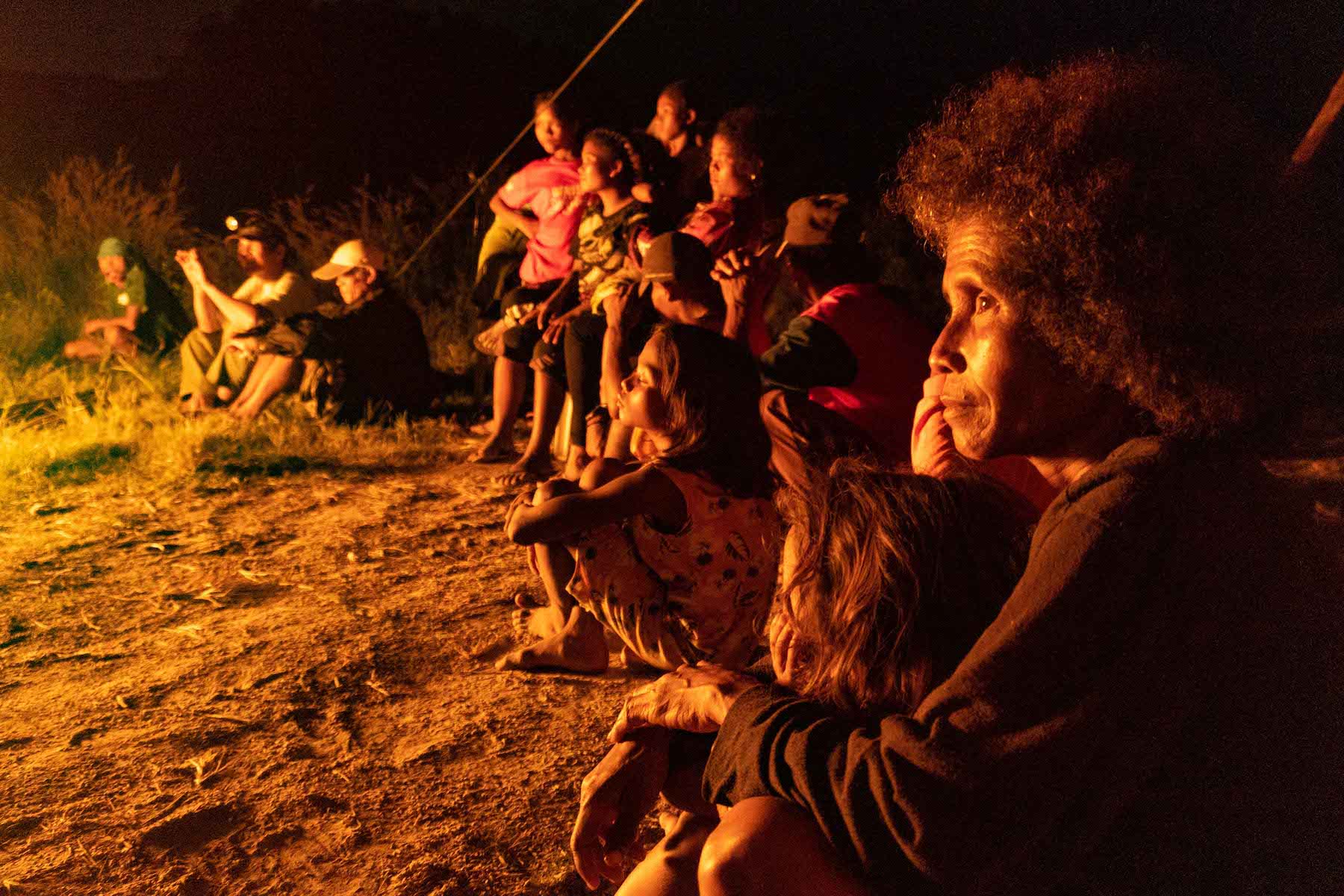

Aeta women perform a traditional dance during a gathering in December 2019, in Sitio Sapang Kawayan, Capas, Tarlac. Their dance mimics the movement of animals. The Aetas perform their dances for entertainment and rituals. (Photo was taken in 2019 by Bernice Beltran)

When a super typhoon hit the Philippines in November 2020, a tree in front Danilo's hut fell. Sand also buried a well where Danilo gets his water. (Photo by Bernice Beltran)

When a super typhoon hit the Philippines in November 2020, a tree in front Danilo's hut fell. Sand also buried a well where Danilo gets his water. (Photo by Bernice Beltran)

Impact of the pandemic

In March 2020, the Philippine government imposed a strict lockdown aimed at curbing the spread of the new coronavirus.

The Aetas were among the most affected by the strict health protocols. They were not able to bring their produce to market.

Some relied on food rations, but it stopped when health restrictions eased sometime in June.

Danilo started to make charcoal to survive while his neighbors picked what they could get from the remaining trees and shrubs in the village.

Aeta children peel off the skin of banana buds. Banana trees grow abundantly in the tribe's ancestral land in Capas, Tarlac. (Photo was taken in 2019 by Bernice Beltran)

Aeta children peel off the skin of banana buds. Banana trees grow abundantly in the tribe's ancestral land in Capas, Tarlac. (Photo was taken in 2019 by Bernice Beltran)

There were those who were still able to tend to their farms but bring the produce to the town center has become arduous because of the construction project. Many areas have become “off-limits” to the Aetas.

“This place does not feel like home anymore,” said Danilo. “I can’t go anywhere.”

When a series of strong typhoons hit the country in November, Danilo lost the roof to his hut.

“I lost my farm. What is there to fight for?” he said when asked if he would join demonstrations to demand that their land be given back to them.

He said what he wants is “to move to a place where my family and I can live peacefully.”

Danilo's wife stands outside the couple's hut in Sitio Alli. (Photo by Bernice Beltran)

Danilo's wife stands outside the couple's hut in Sitio Alli. (Photo by Bernice Beltran)

This report was produced with the support of

InterNews’ Earth Journalism Network.

Text and Photos by Bernice Beltran

Published March 3, 2021

© Copyright MMXXI LiCAS.news

A boy plays as he and his relatives spend time in the afternoon in Sapang Kawayan, a tribal settlement in the outback of Capas, Tarlac. (Photo was taken in 2019 by Bernice Beltran)

A boy plays as he and his relatives spend time in the afternoon in Sapang Kawayan, a tribal settlement in the outback of Capas, Tarlac. (Photo was taken in 2019 by Bernice Beltran)