The Galwan clash of India and China: Duplicity, brutality, and vengeance

Both countries appear to be downplaying the violence, withholding information in face-saving attempts at de-escalation

A June 15 clash in the Galwan Valley of northern India resulted in the deaths of 20 or more Indian and 35 or more Chinese soldiers, according to reporting and sources. Both countries appear to be downplaying the violence and withholding information in face-saving attempts at de-escalation even as the Chinese Foreign Ministry claimed the entire valley as its territory and satellite photos from June 22 show a new Chinese encampment in Indian territory at the spot of China’s attack.

To deter the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) in future, international economic sanctions should be imposed, and India should seek closer defense cooperation with countries like the United States, Japan, Australia, Britain, France, and Germany, as well as with international organizations such as the European Union (EU) and the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN).

The political fallout from the border clash, the bloodiest between China and India since 1967, is a mix of solemn commitments to defend territorial sovereignty and misinformation by China and to a lesser extent in the highly partisan politics of India.

Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) claims a strong defense of the nation from China while trying to downplay the incursion. On June 20, the prime minister went so far as to claim that China did not enter India’s territory. But satellite photos of Chinese soldiers on India’s side of the de facto border is problematizing that message. Despite analysts seeing Modi as stronger on defense, Rahul Gandhi of the competing Indian National Congress (INC) has used the Indian army’s retreat to tar Modi as soft on China.

China too is quietly disputing the BJP’s account. Independent military analyst Song Zhongping, according to The New York Times, said India’s claims of the Chinese death toll were too high but the correct figure would not be released “to avoid stimulating intense sentiment in India.”

(shutterstock.com photo)

(shutterstock.com photo)

Strategic context

Galwan Valley is on the border of China-occupied Aksai Chin and India-occupied Ladakh. Over 100 km southeast of Galwan are other disputed parts of the de facto border, including a large saltwater lake called Pangong Tso and Demchok village. “The security forces posted in the region always show restraint, but people of Ladakh always confront the Chinese whenever there is an intrusion attempt,” according to a former Ladakh official. “In areas like Demchok and Chushul, a lot of grazing land has been intruded upon by the Chinese.”

Ladakh is the part of India-administered Kashmir that borders Aksai Chin. Kashmir is getting pressured by not only China from the northeast, but Pakistan from the northwest. To the immediate north of Ladakh is the Siachen Glacier, occupied in 1984 by the Indian Army, and held against Pakistan at the cost of $1 million per day. To the northwest of Siachen is the Shaksgam tract, ceded by Pakistan to China in 1963.

To the west of Shaksgam is Pakistan-occupied Gilgit-Baltistan, a choke-point for the $62 billion China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC). Gilgit-Baltistan is essential for China’s direct access to the Indian Ocean. But China and Pakistan’s rights to the area are in question. Residents of the territory have little say in their own governance and fear growing Chinese influence. India claims Gilgit-Baltistan as its own, and concludes that therefore CPEC challenges Indian sovereignty.

Galwan provides China with a military overlook on India’s Darbuk-Shyok-Daulat Beg Oldi (DSDBO) road between Leh and the Karakoram Pass. Started in 2001, the road links India’s military facilities near the border. This and other planned strategic road-building slated for completion in 2022, provoked repeated protests from China.

Thus, the Sino-Indian clashes along the de facto border with Aksai Chin have a strategic importance beyond just the square kilometers taken in June, or even those taken in the 1962 war. CPEC, the biggest of China’s Belt & Road initiatives, provides all of China with a lifeline if its access to its near seas were cut in an emergency. India’s claims to China-occupied Aksai Chin and Pakistan-occupied Kashmir and Gilgit-Baltistan are therefore perceived by China as a strategic threat. For the rest of the world, they are a strategic opportunity.

Fueling the conflict is a refusal by China to demarcate the border throughout history. When the British ruled India, China rejected all five proposals between 1846 and 1914 to do so. In the 1950s, Nehru sought to confirm the border with Zhou Enlai, who assured him that Chinese maps showing large parts of India as Chinese territory were “outdated”, and the McMahon line was an “accomplished fact.” Then in 1957 China surprised India by announcing that it had built a road across Aksai Chin between Xinjiang and Tibet. In 2003 China seemed ready to demarcate the border through an exchange of maps but after military officials briefly made the exchange, the Chinese officials took their map back.

General Secretary Xi Jinping has taken a similarly expansive view of China’s borders with India and increased pressure on many of them. As a result, PLA troops have engaged in standoffs with Indian troops in 2013, 2014, and 2017.

India has since its independence in 1947 sought to maintain a strong military and foreign policy of nonalignment and self-reliance. On June 22 Hindustan Times reported that the mood of the Indian government was appreciative of President Donald Trump’s stated support after the Galwan attack, but that a sense of self-reliance remained dominant in New Delhi. “I have my battalions lined up with armoured personnel carriers and artillery,” said a senior minister to the paper. “India will not instigate or precipitate any skirmish but will reply to any transgression. The days of LAC nibbling are over. This is a battle of nerves and India is prepared to wait, come snow, come sunshine.”

The 1962 war’s cease-fire line was recognized in a 1993 agreement as the Line of Actual Control (LAC), or de facto border, between India and China. A Chinese map from 1962 shows the border about 5 km into India from the location of the clash on June 15.

A photo of an Indian military memorial in honor of Indian soldiers who fought Chinese troops in 1962. (shutterstock.com photo)

A photo of an Indian military memorial in honor of Indian soldiers who fought Chinese troops in 1962. (shutterstock.com photo)

Rising military risks from China, and Russia’s dependence on exports to the country, will increase pressures on India to distance itself from its historical friendship with Russia, end its nonalignment and side with other democracies and allies seeking to balance against China’s rise: the United States, Japan, Australia, and increasingly Britain, Germany, France and the EU. ASEAN members such as the Philippines, Vietnam, and Indonesia are also possible allies against China in that China’ 2009 claim to the South China Sea is restricting their maritime rights.

Competing stories of the clash

The official story from New Delhi is that 20 Indians died in the clash on June 15. Prime Minister Narendra Modi claimed that the Chinese troops never strayed into Indian territory. This appears incorrect in light of satellite photos from May 22 to June 22, if not the history of Aksai Chin, which was fully occupied by China in the Sino-Indian war of 1962.

A satellite photo from May 22 shows 15-20 Chinese soldiers around a large tent set up on the bank of the Galwan River near Patrol Point 14, about 137 meters inside Indian territory from the LAC. Another photo on June 16, one day after the attack, shows what may be debris. By June 22, tents and walls have been erected on the Chinese-occupied bank of the river, across from which is a single wall on the Indian-occupied bank. That Chinese encampment disrupts the ability of the Indian military to reach Patrol Point 14 (PP14), which Indian soldiers previously reconnoitered on a regular basis.

Modi’s statement surprised Indian analysts who point to all of Aksai Chin’s 38,000 square kilometers as occupied. China also attempted to occupy India’s state of Arunachal Pradesh in 1962, but withdrew in 1963.

A photo of an Indian military memorial in Ladakh. (shutterstock.com photo)

A photo of an Indian military memorial in Ladakh. (shutterstock.com photo)

China continued to press on India’s border during the latter’s 1965 war with Pakistan. Starting in 1962 and 1966 respectively, Pakistan and China supported Naga secessionists in India’s northeast. In 1967 China attempted to stop India from building a fence at Nathu La near Doklam, but was turned away through fighting in which India lost 200 men and China lost 300. Chinese pressure on India subsided as the PLA shifted its attention to its Manchurian border, where Russian troops were building up in preparation for the 1969 war.

An Indian army convoy moving along the Srinagar-Ladakh Highway on June 18 following deadly clashes along the disputed border with China. (shutterstock.com photo)

An Indian army convoy moving along the Srinagar-Ladakh Highway on June 18 following deadly clashes along the disputed border with China. (shutterstock.com photo)

Perception management

Perhaps to avoid war, India seeks to present the current clash in mild terms as a relatively fair fight, though one in which Chinese troops were aggressors. Even lacking details and in the context of at least some apparent misinformation, the Indian deaths thoroughly angered the Indian public, whose demonstrations put pressure on the government towards economic or even military retaliation.

There is a politically-driven lack of trust in the prime minister by the INC, whose analysts perhaps hypocritically claim to see him as too close to China. In a June 6 article, Bharat Karnad estimated that the most recent of China’s incursions took 35-40 square kilometers of Indian land, bringing the total recent losses to more than 1,200 square kilometers.

Forget condemning China, the PM is too afraid to even talk about it in his national address. #StopBhaashanTakeAction pic.twitter.com/2uxbczGirr

— Congress (@INCIndia) June 30, 2020

Reuters and The Wall Street Journal initially reported relatively staid versions of the June 15 attack. Other outlets reported a surprise attack by China using nail-studded rods, spears and swords, and a surprise Indian counterattack that left dozens of Chinese dead. On June 27, the BBC reported that China planned to deploy martial arts trainers to the LAC and the next day, Al Jazeera reported that they were deployed on the day of the clash.

In order to minimize risks of escalation between the two nuclear-armed countries, agreements in 1996 and 2005 require that soldiers of China and India not use firearms during interactions near the LAC. Indeed, video evidence shows soldiers on both sides scuffling without firearms. In early May, for example, the two sides engaged in a violent shoving match near Pangong Lake. Another video, below, emerged on June 22, that showed a shoving match in Sikkim.

Indian-Chinese soldiers brawl in Sikkim (Video credit: NDTV)

Indian-Chinese soldiers brawl in Sikkim (Video credit: NDTV)

China’s premeditation

The evidence points to pre-planning of the Galwan clash by China . From at least May 5, the Indian military and satellite imagery recorded a buildup on the Chinese side of the LAC of armored personnel carriers, self-propelled artillery, and up to 35,000 soldiers across its border from India’s Ladakh region, including at Galwan, Pangong Tso, Gogra-Hot Springs, Depsang, and Daulat-Beg-Oldie. “At Depsang, Chinese armoured formations have amassed along the LAC, while a 2-km deep incursion has taken place near Gogra, where PLA troops are deployed,” according to the Economic Times of India.

June 22 satellite photos show four Chinese cranes, two bull-dozers and what appears to be a road leveller at Galwan. India sought to mirror this buildup on its side, including through a current deployment of up to 45,000 soldiers.

Satellite image from June 22 shows approximately 200 Chinese soldiers, plus new structures, on Indian territory past the Line of Actual Control (LAC) near Patrol Point 14, Galwan Valley, eastern Ladakh. (Photo by Maxar Technologies via Reuters)

Satellite image from June 22 shows approximately 200 Chinese soldiers, plus new structures, on Indian territory past the Line of Actual Control (LAC) near Patrol Point 14, Galwan Valley, eastern Ladakh. (Photo by Maxar Technologies via Reuters)

Some Indian analysts believe that PLA leaders in the Western Theater Command (WTC), including Gen. Zhao Zongqi and Lt. Gen. Xu Qiling, engineered the conflict to promote themselves within the Chinese Communist Party (CCP). They believe the same incentives drove the Doklam conflict in 2017. This story is supported by a U.S. intelligence assessment but should not absolve Secretary General Xi Jinping, whose responsibility it is to reign in his subalterns. According to the assessment and perhaps purposefully redolent of the Sino-Vietnamese war of 1979 in which he took part, Gen. Zhao in the recent clashes reportedly sought to “teach India a lesson.”

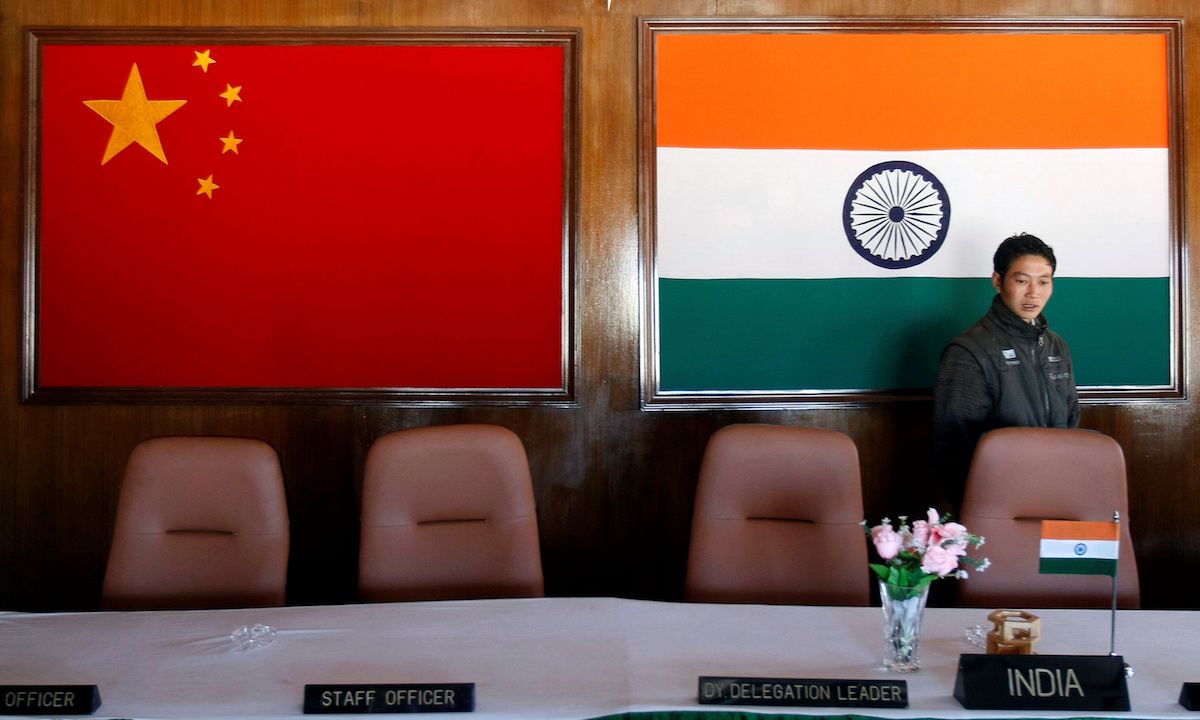

A file image of man walking inside a conference room used for meetings between military commanders of China and India, at the Indian side of the Indo-China border at Bumla, in the northeastern Indian state of Arunachal Pradesh, Nov. 11, 2009. (Photo by Adnan Abidi/Reuters)

A file image of man walking inside a conference room used for meetings between military commanders of China and India, at the Indian side of the Indo-China border at Bumla, in the northeastern Indian state of Arunachal Pradesh, Nov. 11, 2009. (Photo by Adnan Abidi/Reuters)

China and India were allegedly in the process of de-escalation and pullback when China on June 15 unilaterally set up one or two tents near PP14, at a bend in the Galwan River. The land is claimed by India, whose soldiers set the tent on fire, according to multiple media accounts and a source, and in response the Chinese brutally attacked.

After a tent was “removed”, another story relates that, armed lightly with clubs, the Indians could not effectively fight back. Several were killed on the spot by the better-armed Chinese soldiers. Other Indians fled back to a base camp 9 km distant to alert the others. Some say that the Chinese soldiers were unfamiliar to the Indian soldiers, who had developed good relations with the prior group of Chinese.

Indian Border Security Force (BSF) soldiers guard a highway leading towards Leh, bordering China, in Gagangir on June 17. (Photo by Tauseef Mustafa/AFP)

Indian Border Security Force (BSF) soldiers guard a highway leading towards Leh, bordering China, in Gagangir on June 17. (Photo by Tauseef Mustafa/AFP)

Still another story by an Indian television personality in The Washington Post on June 22 states that Chinese soldiers beat Col. Santosh Babu, and his soldiers fought back, pinning several Chinese to the ground. Col. Babu then told his soldiers to relent, and the Chinese fled back to their side of the LAC. All were armed with assault rifles according to this account. There were two tents, and after the Chinese fled, the Indians dismantled them.

A senior Indian official, according to this account, said that at 9 p.m., 300 Chinese in riot gear and armed with rocks returned to PP14. A call for reinforcements brought another 40 Indians from the base, 9 km distant. Col. Babu was then hit by a blunt object and fell 20 feet to his death.

“By the end, 30 Indian soldiers were battling 250 Chinese troops in bloody hand-to-hand combat, according to government officials. As they fought in sub-zero temperatures, stones began to unravel from the mountainside and the soil came loose. Several soldiers fell into the gush of the Galwan River.… Chinese soldiers who had been held back by the Indians escaped. No shots were fired by either side. Apart from the protocol, because of the eyeball-to-eyeball nature of the battle, pulling out a gun could have meant that ‘friendly fire’ would kill one of their own.”

Twelve PLA soldiers were killed, including the battalion commanding officer, according to the writer. China captured 10 Indian soldiers. This Washington Post story appears to be based on a single official source and does not refer to other competing stories.

Stories also diverge as to whether Indians who found themselves in the freezing river were there as a result of fleeing the Chinese, or as a result of being pushed by the Chinese. From PP14 to the river below is a steep drop of over 100 meters.

A West Bengal tribute for Indian soldiers killed in clashes on the contested India-China border. (shutterstock.com photo)

A West Bengal tribute for Indian soldiers killed in clashes on the contested India-China border. (shutterstock.com photo)

That night and into the next morning, according to one source, the Indians along with Gurkhas and Sikhs, allegedly counter-attacked two isolated Chinese positions along a road with the advantage of surprise and their own kirpans (daggers), kukris (machetes) and bayonets. This source claims that Indian soldiers used explosives to cause the landslide onto a Chinese position to even the score. Some Indian reporting refers to the landslide as an act of God, or omits it altogether. Minister of roads and highways V.K. Singh ascribes the landslide to 600 people who he says were fighting at the location.

This source and reporting claims that instead of just 20 Indians killed, 23 Indians were killed, 110 injured, and at least two dozen suffered from life-threatening injuries. Indian media and U.S. intelligence estimated at least 45 Chinese casualties, with 35 of those killed and eight wounded. Minister Singh asserted that Indian troops had captured Chinese troops but did not specify the number.

This alleged Indian vengeance was extracted according to one source by the military leader on the ground, Lt. Gen. Harinder Singh, and without the knowledge of the Indian army’s higher headquarters. When higher authorities called him repeatedly throughout the night, he instructed his communications chief to tell them that he was unavailable due to ongoing operations.

This is how India honours its fallen soldiers, while China hides its fallen soldiers. They don’t get wrapped in their national flag. Oh they can’t be because PLA is CCP army. @HuXijin_GT covers up the hundreds of PLA soldiers killed by saying its goodwill pic.twitter.com/Bqj65ZRHsf

— Yusuf Unjhawala 🇮🇳 (@YusufDFI) June 20, 2020

A need for stronger alliances and transparency

The competing stories spawned by a lack of reporter access to soldiers who were involved in the Galwan clash indicate attempts at information operations by both China and India, as well as by the INC.

But regardless of which story one believes, China’s role in creating the border conflict with India, from refusing to demarcate the border as far back as the 19th century, to initiating the 1962 war, and undeniable continued pushing of boundaries through incrementalism and grey zone tactics today, should be condemned by the international community. The response should include economic sanctions and the holding of China’s leadership personally responsible. Xi Jinping, Zhao Zongqi, and Xu Qiling should all be subject to Magnitsky and other international sanctions for their roles in dangerously increasing tensions between the two nuclear powers.

India’s historic and continued self-reliance with respect to China and Pakistan, and its attempt to match Chinese forces at incursion points, is admirable. Joint patrols with Japan and France, and a shared bases agreement with Australia, all in 2020, are positive. But they are not enough to stop China.

China and Pakistan are allied, and despite India’s self-soothing reporting on its stronger mountain forces, China has nuclear, air and naval superiority. India’s lack of treaty defense allies plays into China’s strategies of incrementalism and divide-and-conquer and explains, along with Chinese influence in the country, why India is desperate to limit escalation even at the cost of regular losses of territory. India’s military and alliance weaknesses all but invite a disastrous two-front war launched by China and Pakistan.

A better strategy for India and democracies globally would be to join forces with allies that seek to balance against the alliance between, and limit the influence of, China, Pakistan, Russia, Iran and North Korea. Joining forces against these aggressive countries will not in any way compromise the autonomy of India, but will rather ensure its defense.

Anders Corr holds a Ph.D. in government from Harvard University and has worked for U.S. military intelligence as a civilian, including on China and Central Asia. The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official editorial position of LiCAS.news

© Copyright 2020 LiCAS.news

This article was published July 3, 2020.

The India-China border at Nathula Pass in this image taken Jan. 10. (shutterstock.com photo)

The India-China border at Nathula Pass in this image taken Jan. 10. (shutterstock.com photo)