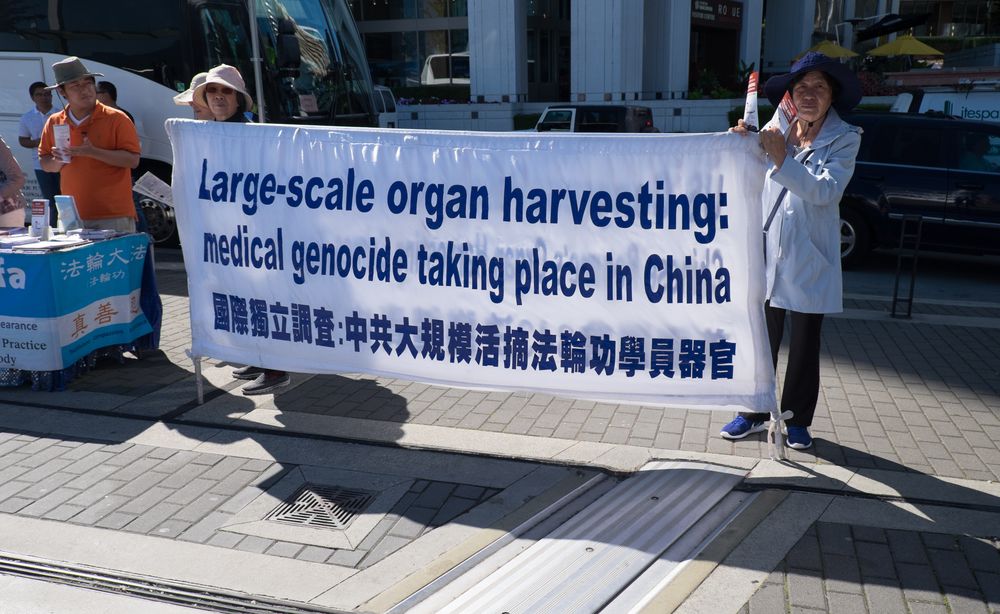

Turning a blind eye to forced organ harvesting in China

A tribunal in London found the practice in China against prisoners of conscience to be a near-genocidal crime against humanity

In the British House of Lords on March 2, questions to ministers included one from Lord Hunt of Kings Heath to ask the British government “whether the proposed United Kingdom autonomous global human rights Magnitsky-style sanctions regime will apply to persons engaged in (1) illegal organ trafficking, or (2) obtaining organs for transplant without consent.”

Lord Hunt wrote to me afterwards:

“The horrific enforced organ donation trade in China is appalling. I will keep on pressing the Government until they start to take some action.”

The problem in China is indeed immense, and there is increasing attention to the issue in part because of how practitioners of the Falun Gong spiritual practice have been targeted for forced organ harvesting based on their beliefs.

There is plenty of evidence of forced organ harvesting in China, and likely some overlap between the Falun Gong and death row inmates as organ sources.

“Several articles have drawn attention to the double meaning of the term ‘executed prisoner,’” according to Macquarie University clinical ethicist Wendy Rogers. “And independent investigators have identified that they include prisoners of conscience, who are executed for their organs without due process, as well as death-sentence prisoners whose organs are harvested after judicial execution.”

Front view of First Affiliate hospital of Chongqing Medical University in China which has allegedly carried out organ harvesting. (shutterstock.com photo)

Front view of First Affiliate hospital of Chongqing Medical University in China which has allegedly carried out organ harvesting. (shutterstock.com photo)

By some estimates, approximately 90 percent of kidney transplants in China are sourced from “death row.” China actually admitted to sourcing organs from death row inmates between 2005 and 2015. Today, they generally deny sourcing organs from death row, though at a 2017 Vatican conference discussed by Rogers further below, they at least once admitted to continuing the practice of sourcing organs from prisoners.

A global problem

But one would be remiss not to first observe that the problem goes well beyond death row inmates, prisoners of conscience or even China. Our critical attention to forced organ harvesting should arguably include countries like Pakistan, India, the Philippines, Bolivia, Brazil, Peru, Colombia, Moldova, Turkey and Iraq. The poor from these countries more often than elsewhere feel compelled by their economic circumstances to accept loss of an organ in order to make ends meet. There is an element of force to economic compulsion.

Approximately 10 percent of the 100,000 organ transplants annually are via “transplant tourism” according to experts, where wealthy recipients are put at the head of the line in poorer countries where organs can be found cheaply, and in which local poor recipients suffer from lack of supply. In Pakistan in 2006, for example, foreigners received approximately two thirds of the 2,000 kidney transplants, most likely from poor donors who felt economically compelled to relinquish an organ.

According to the Australian Health Department, between 2001 and 2014, at least 53 Australians went to China for organ transplants. That number could be an understatement. A single doctor in Canada, according to Professor Maria Cheung at the University of Manitoba, reported at least 50 patients who went to China for transplants in 2014 alone.

Organ transplant tourists from common importing countries like the United States, Europe, Canada, Australia, Japan, Israel, Saudi Arabia and Oman could save more lives than their own, with the money they spend to extract an organ from someone who could be killed abroad just to source a kidney, liver, heart, lungs or cornea.

The culpable include the traffickers and brokers of organ commercialism, but also the billions of people who fail to proactively donate their organs should they no longer need them due to accident or death.

Global solutions

The ethics of the global organ trade is uncomfortable because it reveals the lack of care and depth of selfishness in the human character when confronted with its own survival. As with any character problem, there is no easy solution. But international precedents calling for stronger government action and emerging legal norms against transplant commercialism and forced organ harvesting are starting to point the way.

The World Health Assembly (WHA) resolved in 2004 that member states should “take measures to protect the poorest and vulnerable groups from transplant tourism and the sale of tissues and organs, including attention to the wider problem of international trafficking in human tissues and organs.”

In 2008, the Declaration of Istanbul on Organ Trafficking and Transplant Tourism included a statement by its steering committee that said: “The legacy of transplantation is threatened by organ trafficking and transplant tourism. The Declaration of Istanbul aims to combat these activities and to preserve the nobility of organ donation. The success of transplantation as a life-saving treatment does not require — nor justify — victimizing the world's poor as the source of organs for the rich."

There is some legislative progress against forced organ harvesting and transplant commercialism. Spain, Israel, Norway, Taiwan, and Italy have enacted legislation to bring their practices into conformity with principles against transplant commercialism.

In June 2016, the U.S. House of Representatives passed a resolution calling for an annual State Department report on implementing an existing law barring visas to Chinese and others engaged in forced organ harvesting. The following month, the European Parliament passed a declaration that called for an independent investigation in China of “persistent, credible reports on systematic, state-sanctioned organ harvesting from non-consenting prisoners of conscience”.

A bill in Canada introduced in 2015 has been wending its way through the Senate and House of Commons. If finally enacted, it would create new offences related to human organ trafficking, and bar foreign nationals from Canada who engaged in human organ trafficking.

While these building norms and legislative acts are progress, much more needs to be done by the world community, and more quickly.

(pixabay.com photo)

(pixabay.com photo)

(shutterstock.com photo)

(shutterstock.com photo)

Forced organ harvesting in China

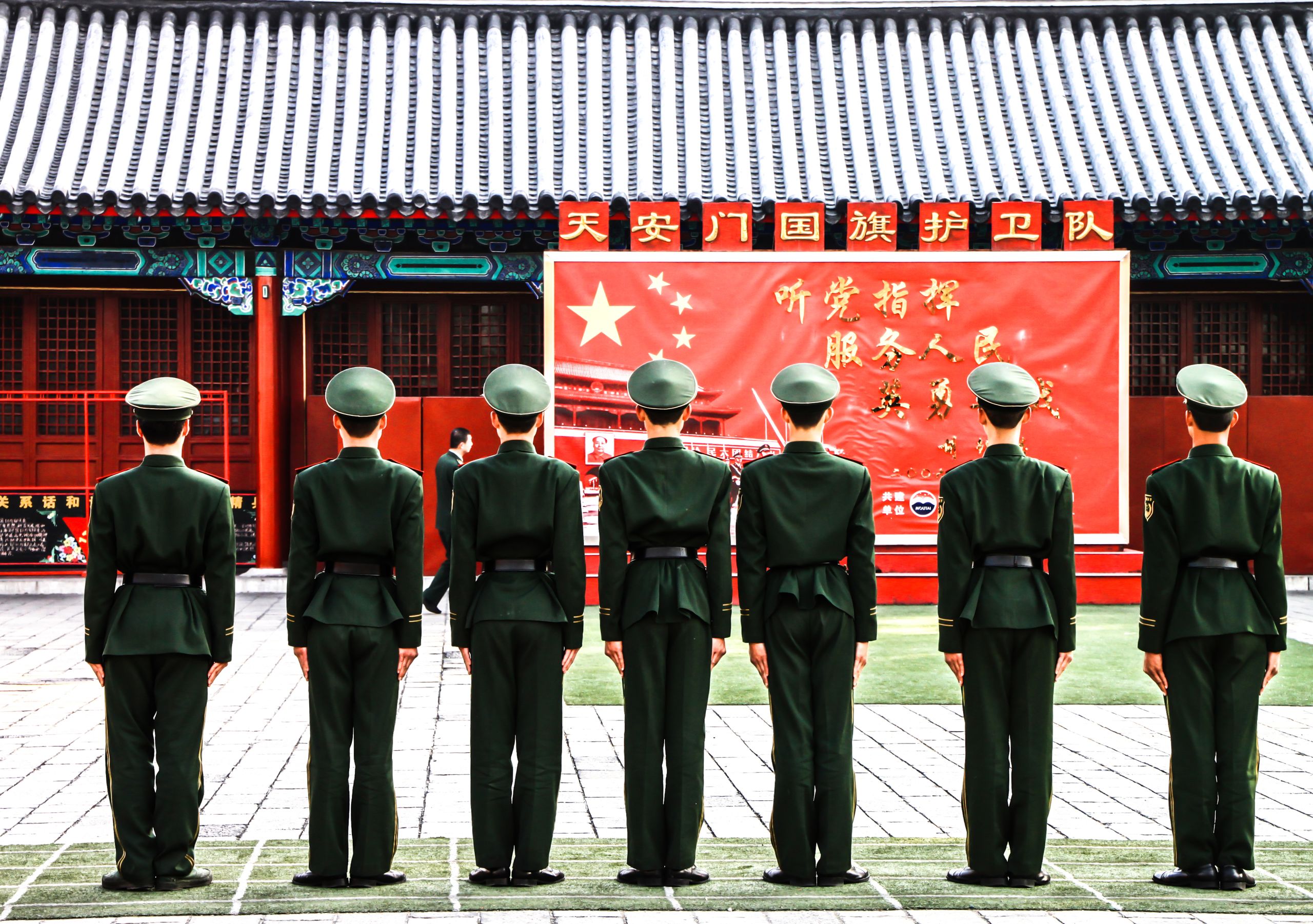

The focus of global concern about forced organ harvesting and transplant commercialism has increasingly centered on China due to building evidence that the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) is singling out prisoners of conscience, predominantly Falun Gong practitioners, for organ harvesting that results in prisoner death.

Lord Hunt’s incisive questioning on March 2, for example, was followed by additional questions from the lords who pressed a minister of the Boris Johnson government to take a stronger stand on China’s organ harvesting.

One question from Baroness Lindsay Northover referred to a March 1 report totaling 562 pages (including appendices) and full of evidence of forced organ transplantation and blood draws from prisoners of conscience.

While nearly all the evidence collected by the China Tribunal points to China’s forced organ harvesting against Falun Gong practitioners, there is increasing worry about the same practices against Uyghurs and other Turkic Muslims.

According to Professor Cheung, 19 million Uyghurs have been subjected to forced biodata collection, including DNA and blood samples that would be useful in matching organs to recipients. There is one claim that Saudi patients sought “halal” organs from Xinjiang. In 2017, the Kashgar airport in Xinjiang established a priority lane for organ transfers. China’s Turkic Muslim population, approximately 1-3 million of whom have been detained in “reeducation centers” in Xinjiang, is seen by experts as particularly vulnerable to forced organ harvesting.

From left: Organ harvesting researchers; former Canadian MP David Kilgour and Canadian human rights lawyer David Matas with U.S. investigative writer Ethan Gutmann. (Photo supplied)

From left: Organ harvesting researchers; former Canadian MP David Kilgour and Canadian human rights lawyer David Matas with U.S. investigative writer Ethan Gutmann. (Photo supplied)

There is also some worry among experts of forced organ harvesting against Christians and Tibetans in China. Ethan Gutmann, who in 2014 published a book with Random House on the subject, estimated that the organs of 65,000 Falun Gong, and 2,000-4,000 Uyghurs, Tibetans and Christians, were harvested between 2000-2008 alone.

Then in 2016, Gutmann with Canadian lawyers David Kilgour and David Matas claimed that China performed an estimated 60,000-100,000 organ transplants per year, and that the only plausible source of so many organs was through forced organ harvesting.

Probably due to this shocking practice, organs can be procured in China within weeks or even days according to Professor Cheung. In this way, transplant tourists from wealthy countries can skip multi-year waitlists that could otherwise result in their deaths. Cheung agrees that the quantity of organ transplant operations in China cannot be supplied by voluntary donations and death row executions.

Prisoners of conscience, in particular from the Falun Gong practice, are the main source for the forced organ harvesting that continues today according to evidence released March 1 from the China Tribunal.

The tribunal is composed of a highly-respected group of judges, lawyers and professors. Sir Geoffrey Nice QC, who practiced at the International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia (ICTY) between 1998 and 2006 led the tribunal. He was lead prosecutor against Slobodan Milošević, former president of Serbia. He has since worked in connection to permanent International Criminal Court cases on Sudan, Kenya, and Libya. A Briton, he serves as a part-time judge at Old Bailey and between 2009 and 2012 he was vice-chair of Britain’s Bar Standards Board.

Other members of the China Tribunal include Professor Martin Elliot (University College London), lawyer Andrew Khoo (co-chair of the Constitutional Law Committee of the Bar Council Malaysia), and Professor Arthur Waldron (University of Pennsylvania).

The China Tribunal - Final Judgment (2019)

Former international war crimes prosecutor Sir Geoffrey Nice QC during the China Tribunal. (Photo by Justin Palmer)

Former international war crimes prosecutor Sir Geoffrey Nice QC during the China Tribunal. (Photo by Justin Palmer)

Genocide and crimes against humanity

The China Tribunal report includes analysis, witness and expert testimony, as well as maps showing the location of detention centers and organ transplant hospitals. The tribunal released a summary judgment in June 2019, but on March 1, also released the full 562-page report.

While not establishing intent, the tribunal found two elements of the crime of genocide against the Falun Gong, namely “killing members of the group” and “causing serious bodily or mental harm to members of the group.”

Some experts nevertheless do believe the intent of the People’s Republic of China (PRC) is deadly. According to Edward McMillan-Scott, member of the European Parliament from 1984-2014: “I believe that the intent against Falun Gong is criminal and the goal is death through evisceration.”

The China Tribunal held in London. (Photo by Justin Palmer)

The China Tribunal held in London. (Photo by Justin Palmer)

Furthermore, the tribunal found that: “Commission of Crimes Against Humanity against the Falun Gong and Uyghurs has been proved beyond reasonable doubt by proof of one or more of the following, legally required component acts: murder; extermination; imprisonment or other severe deprivation of physical liberty in violation of fundamental rules of international law; torture; rape or any other form of sexual violence of comparable gravity; persecution on racial, national, ethnic, cultural or religious grounds that are universally recognized as impermissible under international law; and enforced disappearance, in the course of a widespread and systematic attack or attacks against the Falun Gong and Uyghurs.”

The tribunal published evidence that: former president Jiang Zemin, in power from 1993-2003, ordered harvesting of organs from Falun Gong practitioners; doctors from leading Chinese transplant hospitals have knowledge that organs are available from Falun Gong detainees; organ harvesting was done on live prisoners, resulting in their deaths; there are extraordinarily short wait times for organs in China; and unwilling Falun Gong donors are likely the main source of organ supply in China.

The tribunal also concluded “with certainty” that acts of torture were inflicted on both Falun Gong and Uyghur detainees, and that both have been subjected to forced medical tests, the focus of which were their organs.

Targeting the Falun Gong for forced organ harvesting

Falun Gong is a Buddha-school form of meditation and qigong movements that was popular in China during the 1990s. After growing official repression, its practitioners held an orderly 10,000-person demonstration in Beijing on April 25, 1999 that was an unwelcome surprise for the CCP. Falun Gong had up to 70 or 100 million followers at the time, and its popularity was seen by CCP leadership as a threat to the party’s sway over Chinese society.

It wasn’t long until official resistance to Falun Gong became persecution, including what seems almost too horrible to be true: forced organ harvesting from live prisoners for transplant. After the operation, the prisoners do not survive.

Forced organ harvesting has fallen particularly hard on the Falun Gong not only due to their being labeled as an enemy of the state, but because their organs are seen as generally clean and healthy compared with organs of other prisoners who are more likely from poor backgrounds, or may have abused smoking, alcohol or drugs. Chinese transplant surgeries can, therefore, discreetly market themselves as the cleanest source of organs globally when compared with other poorer countries that have no such unethical screening process for the healthy practices of their “donors”.

According to McMillan-Scott: “Of particular concern is that only Falun Gong — who neither smoke nor drink — are routinely blood-tested and blood-pressure tested in prison: This is not for their well-being. They thus become the prime source for the live organ transplant trade: More than 40,000 additional unexplained transplants have been recorded recently in China since 2001. More recently, there is evidence that organ harvesting is being practised not only on Falun Gong and Uyghur prisoners, but also on Tibetans, following the 2013 uprising and repression there.”

A Chinese woman practices Falun Dafa (Falun Gong) meditation practices in the U.S. (shutterstock.com photo)

A Chinese woman practices Falun Dafa (Falun Gong) meditation practices in the U.S. (shutterstock.com photo)

The practice of targeting Falun Gong for organ harvesting is disturbingly widespread among Chinese health professionals. According to the World Organisation to Investigate the Persecution of Falun Gong (WOIPFG), which has investigated the issue since 2006, more than 7,000 medical professionals in China participate in forced organ harvesting.

While since 2010 China claimed to be reforming its sourcing of organs, and in 2015 China announced that voluntary hospital donors have been the sole source of organs, analysts using statistical methods in the journal BMC Medical Ethics found indications in Chinese organ transplant data of “human-directed data manufacture and manipulation” as well as “contradictory, implausible, or anomalous data artefacts.”

In other words, China is faking the data.

Forced organ harvesting against Uyghurs, Tibetans and Christians

While most of the evidence in the March 1 China Tribunal report is of forced organ harvesting against the Falun Gong, there are some indicators of such crimes against Uyghurs, Tibetans and Christians.

According to Sarah Cook, a senior research analyst for East Asia at Freedom House: “The large‐scale disappearance of young Uighur men, accounts of routine blood‐testing of Uighur political prisoners, and reports of mysterious deaths of Tibetans and Uighur in custody should raise [the] alarm that these populations may also be victims of involuntary organ harvesting.”

Indicators of forced organ harvesting against Uyghurs include a priority lane at the Kashgar airport in Xinjiang, crematoria, and blood testing that is so widespread it must be government-sponsored, according to the experts cited here. Tibetans have also been subjected to widespread blood “tests” in quantities sufficient for transfusions, including over 90 percent of those imprisoned in the 1990s who were interviewed by researcher Jaya Gibson.

Chinese police near Potala Palace, Lhasa, Tibet on Feb. 14, 2009. (shutterstock.com photo)

Chinese police near Potala Palace, Lhasa, Tibet on Feb. 14, 2009. (shutterstock.com photo)

There is comparatively little evidence of forced organ harvesting against Christians, but according to Ethan Gutmann, whose testimony is paraphrased in the report: “There is enough data to indicate that Christians are a source of organs.” He responds to others who argue that there is no such evidence by saying: “[I] don’t agree that there is lack of evidence that House Christians have been targeted for this. Christian Solidarity Worldwide are not getting a lot of reports of this, but I get other stories.”

A witness named Dai Ying is paraphrased in the report as recalling that in 2003 in the Shansui Labor Camp:

“180 Falun Gong practitioners were x-rayed and had large blood samples taken, urine tests and ‘probes’, plus physical examination. The tests seem to have been performed on Falun Gong practitioners and Christians... but not other prisoners.”

Ethan Gutmann (left) with Edward McMillan-Scott at a 2009 Foreign Press Association press conference, April 28, 2009. (Photo by Jaya Gibson)

Ethan Gutmann (left) with Edward McMillan-Scott at a 2009 Foreign Press Association press conference, April 28, 2009. (Photo by Jaya Gibson)

Gutmann gave a short history of organ harvesting in his oral testimony to the China Tribunal that references Christians. He testified:

“What emerges is that the CCP’s motivation for organ harvesting clearly changes over time: from simply carrying out an order to eliminate Falun Gong, to a public and increasingly global struggle against a recalcitrant movement that will not convert, to a mass cover-up of two decades of organ harvesting crimes. Understanding those shifts requires a historical understanding of the CCP, yet it also calls out for a coherent narrative of the last two decades. It demands that we question the narrative that the Falun Gong persecution was an isolated event. The discovery that ‘Eastern Lightning’ House Christians were also being tested for their organs emerged organically from the interviews with Fang Siyi and Jing Tian (chapter 8 [in Gutmann’s The Slaughter, Random House, 2014]) yet organ harvesting of death-row prisoners began in the 1980s, and that is why I began to suspect that the Uyghurs were the first prisoners of conscience to be harvested and to look closely at the specific CCP reaction to the Ghulja Incident in 1997 (chapter 1) - and later, the specific challenges of the Tibetan resistance (chapter 8).”

Gutmann indicates that one reason we don’t know more about cases of forced organ harvesting against Tibetans is that their leadership is uncooperative.

“In terms of Tibetans, the community is not cooperative because the Dal[a]i Lama is concerned it will lead to an end of discussion with Beijing,” Gutmann told the tribunal.

The expanding scope of persecution from the Falun Gong to other minorities in China is evidenced by the evolution of the party bureaucracy. Sarah Cook told the tribunal of her research into the “610-office”, which she described as an extra-legal party committee and security force that sought to “transform” Falun Gong. It was especially active in 2013 but has continued with significant funding to the present.

She said: “The 610-office mandate has been expanded, it now deals with 23 various quasi-Christian and qigong religions. It is not only the Falun Gong. One of the other things you see happening is the expansion of its mandate to other forms of dissent.”

Cook noted in the testimony that human rights, religious persecution and civil liberties abuse has targeted “Tibetan, Uyghur Muslims and protestant Christians.”

Not all experts believe that Christians are the targets of forced organ harvesting in China. McMillan-Scott gave oral testimony that focused on the targeting of Uyghurs, Tibetans and Falun Gong as opposed to Christians. “For Uyghurs, Tibetans and Falun Gong — their treatment is contrary to the provisions of Article 2 of the Genocide Convention, on the basis that other evidence is credible,” he is summarized as stating. “There is no evidence that House Christians are persecuted as other groups.”

This picture taken on March 14, 2016 shows Amity Dong, a Chinese Falun Gong practitioner and asylum seeker, performing Falun Gong exercises in Bangkok. (Photo by Lillian Suwanrumpha/AFP)

This picture taken on March 14, 2016 shows Amity Dong, a Chinese Falun Gong practitioner and asylum seeker, performing Falun Gong exercises in Bangkok. (Photo by Lillian Suwanrumpha/AFP)

Another expert who testified before the China Tribunal explained why the focus of the Chinese authorities is against the Falun Gong. “Falun Gong are a threat for two main reasons: the first is that their ideas emanate from traditional Chinese culture,” said Yiyang Xia, director of China Policy at the Human Rights Law Foundation (HRLF). “Christian and Catholics are also a threat to the Chinese government, but it is easy for the government to persuade the Chinese people against the beliefs of these minorities by using nationalism (their beliefs emanate from the West),” according to the tribunal’s summary of his remarks. Yiyang Xia noted that the Falun Gong does not at all cooperate with the government, which cannot infiltrate the organization. “Previously, spies sent by the government to investigate the Falun Gong converted to Falun Gong,” he said.

Torsten Trey, executive director of Doctors Against Forced Organ Harvesting (DAFOH), also stated that there is insufficient evidence of forced organ harvesting against Christians to conclude that they are targeted in the same way as Falun Gong. Trey did, however, say that “we see a high risk in this group,” in reference to Christians.

China is hiding something

The China Tribunal report notes that China, and the world more generally, has taken a lax stance towards evidence of forced organ harvesting revealed over the last decade.

According to the tribunal, “the People’s Republic of China has done little to challenge the accusations [of the tribunal] except to say that they were politically motivated lies.”

Bald denials without demonstrations of greater transparency can themselves be indications of wrongdoing. But Chinese authorities went further.

The tribunal, it said, “contended with a pervasive culture of secrecy, silence and obfuscation by the PRC relating to much material that could have helped in the determination of whether forced organ harvesting has occurred in China.”

And the world is turning a blind eye

China’s hiding of its forced organ harvesting is helping the world turn a blind eye to what amounts to crimes against humanity. The China Tribunal stated: “Governments around the world and international organisations, all required to protect the rights of man, have expressed doubt about the accusations, thereby justifying their doing nothing to save those who were in due course to be killed to order.”

And “doing nothing” was on full display in the British House of Lords on March 2.

In response to Lord Hunt of Kings Heath, and several other lords one of whom brought up the China Tribunal report, the government’s Minister of State, Foreign and Commonwealth Office and Department for International Development, twisted and turned to avoid providing solid answers.

The minister, Lord Ahmad of Wimbledon, claimed not to have read the report, even though a preliminary judgement had been available for approximately six months. He claimed to be time-limited at international fora and so unable to raise the issue of forced organ harvesting. And, he claimed to have taken up the issue with the World Health Organization (WHO), rather than with China itself. In answer to one question he made the nonsensical claim that allegations in the report should be raised in the context of the report.

“The short answer to the noble lord is yes; we have taken up direct conversations and consultations with the World Health Organization,” said Lord Ahmad. “I put on record again that the allegations that have been raised in various reports, including the final report conducted by Sir Geoffrey Nice, raise questions that need to be answered in the context of that report. I know the noble Lord is aware that the view of the World Health Organisation remains that China is implementing an ethical, voluntary organ transplant system, in accordance with international standards, although it has now raised concerns about transparency. I assure the noble Lord that we will continue to prioritise this issue and that of human rights within the context of China.”

The British government’s runaround given to the lords on March 2 was decidedly not the prioritization of human rights in China. It also shows how WHO negligence, bordering on complicity, can provide a shield for governments that do not seek to address the difficult issue.

At a December meeting in which China defended its organ transplant practices, according to China’s state-run Global Times, Jose Nuñez, WHO officer in charge of global organ transplantation, told the paper, in summary:

… they received the report produced by Lavee, and it was sent to them [the WHO] repeatedly twice a week. "But we didn't respond," said Núñez [sic], noting that China has already provided efficient data with Global Observatory on Donation and Transplantation.

Núñez said there's nothing to cast doubt on China's data, those data are efficient. "So anything that comes from the magazine or the scientific journal is just his or her opinion," he said.

In addition, the Global Times summarized Nuñez as saying:

"China's organ transplant reform has achieved remarkable results in a short period of time, and China's experience can serve as a model for the entire Asian region and the world."

Francis Delmonico, chairman of the organ transplantation task force at the WHO, is quoted in the Global Times as saying: “The biggest feature of the Chinese experience in organ transplantation is the strong support from the Chinese government, which is an example that many countries should follow."

The WHO, Nuñez and Delmonico did not respond to requests for comment.

WHO’s negligence extends back further. In an interview published in 2012, the WHO Bulletin introduced the article by stating that “China is establishing a new national system for organ donation and transplantation, based on Chinese cultural and societal norms, that aims to be ethical and sustainable.” The rest of the article is an interview with a Chinese official who is given soft-ball questions and whose answers go unchallenged.

The Vatican too has been widely criticized for ignoring China’s forced organ harvesting.

The 2017 Pontifical Academy of Science Summit on Organ Trafficking and Transplant Tourism invited Huang Jiefu, chair of the National Organ Donation and Transplantation Committee, member of the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference (CPPCC), former vice minister of health, and deputy director of a secretive committee that provides healthcare to top CCP cadres.

Huang’s practices came under ethical scrutiny when it became known that he ordered two spare livers in 2005 as backup for a challenging procedure. “It is hard to imagine how this order could have been met in a system that relied solely on organs from prisoners sentenced to death,” wrote Professor Rogers of the transplant operation. “But the order is consistent with a system in which prisoners’ organs are plentiful, immediately available and blood-matched in advance ... waiting for death at the surgeon’s convenience.”

Wendy Rogers, professor of Clinical Ethics at Macquarie University in Australia. (Photo by Chris Stacey/Macquarie University)

Wendy Rogers, professor of Clinical Ethics at Macquarie University in Australia. (Photo by Chris Stacey/Macquarie University)

Rogers wrote that it was thought Huang would not present an accurate and complete depiction of organ sourcing in China at the Vatican conference. “He has given contradictory accounts of organ sources in China for many years,” she wrote, noting that the resulting media coverage caused embarrassment to the Vatican and “apparently led to the cancellation of the Pope’s planned address to the summit.”

Huang admitted that organ transplants from prisoners continue to the present day. “After persistent questions, Huang admitted organ transplants from prisoners still occur,” Rogers wrote about the conference. “He cited the vast size of his country as an impediment to reform.”

(shutterstock.com photo)

(shutterstock.com photo)

Why is the world silent?

Governments, and even more so international organizations like the WHO, have done little to stop forced organ harvesting in China. Why in the case of the WHO would it actually cover China’s crimes by claiming they were “ethical”? And, why would the British government on March 2 draw attention to this obviously fallacious claim as if it were true?

There are numerous potential causes for the silence, the most important and obvious of which are money and trade. But first consider these additional causes.

First, note that the details of this particular form of human rights abuse may be too gruesome for many to contemplate. Killing someone of conscience for his or her organ does not make for pleasant conversation.

Second, China has done such a thorough job at painting the Falun Gong as a “cult”* that some governments and organizations may prefer not to address the issue for risk the “cult” smear could taint them as well. They might prefer to address “easier” human rights issues that more readily gain public sympathy, like racial discrimination (e.g., against the Uyghurs) or political democracy (e.g., in Hong Kong).

*The practice of Falun Gong does not meet the accepted definition of cult.

Third, in an increasingly secular world, mainstream defense of religions that suffer persecution is relatively less interesting to a public that would, for example, sooner use an old church for a gym or night club than for the purpose it was built in centuries past.

China organ harvesting researcher Matthew Robertson. (Photo supplied)

China organ harvesting researcher Matthew Robertson. (Photo supplied)

All of this has to a greater or lesser extent led governments and international organizations to downplay forced organ harvesting. "The issue has been extremely difficult for governments around the world and international organizations, including the World Health Organization and The Transplantation Society, to face squarely,” Matthew Robertson told me by email. “It is a highly inconvenient and uncomfortable topic for their relationship with China.”

Robertson is an academic and Chinese speaker who provided expert testimony to the China Tribunal. The Society of Professional Journalists’ awarded him the Sigma Delta Chi award in 2013 for his reporting on China’s forced organ harvesting.

The Transplantation Society holds annual conferences at which it invites PRC speakers, including the controversial liver surgeon Zheng Shusen as recently as 2018. Zheng was formerly the chairman of the Zhejiang Anti-Cult Association, an organization instituted to campaign against Falun Gong.

According to Rogers, Zheng has made false claims that no organs from executed prisoners were used in his research. In 2017 the journal Liver International retracted an article by Zheng due to his failure to provide evidence that 563 liver transplantations had been done with consenting donors. He has been the lead surgeon in 1,957 liver transplants, including five on a single day.

It beggars belief that Zheng sourced five organs from willing donors on the same day.

Robertson said that the lack of an authoritative voice on forced organ harvesting makes it difficult for the media and human rights organizations to gain purchase. “This avoidance [by governments and international organizations] has flowed through to coverage in major media and by the international human rights groups, and it has all been self-reinforcing,” wrote Robertson.

For money?

Robertson alludes to the “relationship with China” as a reason that governments and international organizations are avoiding the topic of forced organ harvesting. But what exactly is this relationship that obstructs an honest appraisal? I would argue that it is primarily trade, and sometimes the personal gain of western politicians who do business with China.

In 2016, the Australian Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade First Assistant Secretary Graham Fletcher told an Australian Senate committee that he doubted the credibility of allegations of forced organ harvesting. “They are not given credence by serious human rights activists,” he said, and claimed that Falun Gong and Christians were not being executed because of their religious affiliations.

It is telling that Fletcher, one of the world’s most prominent deniers of forced organ harvesting against the Falun Gong, is not a minister of health. Neither is he a minister of human rights (Australia has no such minister). Thus, one must wonder at why he would be so prominent on a health and human rights issue, rather than someone more qualified to comment.

His official competency was foreign affairs and trade, which must therefore be seen as the foundation of Australia’s position on the issue. Fletcher’s facility with China as first assistant secretary of foreign affairs and trade was apparently noticed, and in 2019 he was made ambassador to the country.

Between 2017 and 2018, China was Australia’s top trading partner, at $195 billion Australian dollars, or over 24 percent of its total trade. China’s trade with Australia approximately equaled Australia’s trade with its next three biggest trade partners: Japan, the United States, and South Korea.

The WHO’s lack of response could also be explained by the significant revenues it acquires from China. From 2010-12, China contributed $285 million to international organizations, including $86 million to the WHO in 2019. Most of that sum is based on China’s assessed ability to pay, but $10.2 million is voluntary. Thus, China has considerable influence over the WHO as it could easily withdraw its voluntary contribution and might also withdraw the rest.

It should not be ignored that leaders in places like Australia, and in organizations like the WHO, could also be seeking private benefit from China. Australia’s former trade minister, Andrew Robb, got a consulting job worth Australian $880,000 per year with Ye Ching, a billionaire closely aligned with the CCP. Robb took the position right after he left his government job, in which he was described as the architect of the China-Australia Free Trade Agreement.

The appearance of selling out is not limited to Australia. Chinese companies sought to bribe African officials in Chad and Uganda. The once president of the U.N. General Assembly, John Ashe, was accused of taking $1.3 million in bribes from Chinese businessmen. Then he died, supposedly in a home gym accident. A barbell asphyxiated him in his own home, with charges still pending against the accused businessmen.

Monetary incentives also apply to Britain. When David Cameron left his position as prime minister, he sought to lead a $1 billion China investment fund. It was endorsed by both the British and Chinese governments.

Now under Prime Minister Boris Johnson, the British government is desperately trying to regain its economic feet after Brexit. It needs outside options to trading with Europe that will be especially important in case post-Brexit trade negotiations fail. Trade with China and the United States would then be critical.

(shutterstock.com photo)

(shutterstock.com photo)

Britain has apparently bent over backwards to placate China, as demonstrated most recently in the House of Lords on March 2. Britain is also striving to please China by accepting tainted Huawei equipment in its 5G infrastructure, engaging in talks with China about building high-speed rail in Britain, and progressing a Chinese civil nuclear power design that will likely put a Chinese nuclear power plant on Britain’s own soil and out-compete Britain, Russia and the United States in global markets.

To maximize trade with China, most governments deemphasize Chinese human rights issues in public. Those that don’t, find themselves at the wrong end of threats and canceled trade deals. When Norway awarded the Nobel Peace Prize to democracy activist Liu Xiaobo in 2010, China stalled a trade deal with the country.

(shutterstock.com photo)

(shutterstock.com photo)

China threatened Sweden with unspecified consequences in 2020 when the Swedish culture minister awarded a literary prize to Gui Minhai, an imprisoned Hong Kong bookseller and Swedish citizen. China had already cancelled trade talks with the country the year prior, when Sweden’s PEN organization gave the writer a human rights prize.

Similar incentives apply to any country that seeks to increase trade with China. With $2.1 trillion in imports, and $2.5 trillion in exports (2018), China is one of the world’s top traders, along with the United States and Germany. But unlike these latter two, China is more aggressive in linking its trade to political concessions. Given its greater control over its domestic corporations, China can use trade for leverage much more easily than can governments that lack command economies.

This makes corporations, universities and governments anywhere in the world loath to challenge the PRC on ethical grounds for fear of losing market access. Money talks, while those who really want to make money, stay silent.

The moral imperative to act

Due to the mounting evidence of forced organ harvesting, and I would argue the erosion of ethics that has accompanied it in not only China but the rest of the world such that it needs saying, the tribunal was forced to note that interacting with the Chinese government must be considered interaction with a criminal state.

According to the March report:

“Any person or organization that interacts in any substantial way with the PRC — the People’s Republic of China — including: doctors and medical institutions; industry, and businesses, most specifically airlines, travel companies, financial services businesses, law firms, and pharmaceutical and insurance companies, together with individual tourists; educational establishments; arts establishments should recognize that, to the extent revealed in this document, they are interacting with a criminal state.”

The tribunal is not just calling for the medical establishment to recognize China as a criminal state, and by implication to decrease interaction. It is calling on all of us, including even “arts establishments,” to do so.

The obvious lack of such concern by governments and international organizations that should know better, make it incumbent on regular citizens to act against China’s atrocities.

Yes, check the box and make yourself an organ donor. That will supply the demand for organs from voluntary donors and at least partially obviate the perceived need of some to use questionable Chinese sourcing.

But regular citizens must also demand greater coordinated action by the authorities that is in no way guaranteed. “Assuming they [governments and international organizations] do not do their duty, the usually powerless citizen is, in the internet age, more powerful than s/he may recognize,” the tribunal concludes. “Criminality of this order may allow individuals from around the world to act jointly in pressurising governments so that those governments and other international bodies are unable not to act.”

Regular citizens stepping up

Regular citizens are indeed stepping up.

One of the authors of the BMC Medical Ethics article, the already mentioned Matthew Robertson, will be launching a report with the Victims of Communism Memorial Foundation on this topic on March 10 at Capitol Hill in Washington, DC.

David Matas, author of State Organs: Transplant Abuse in China, spoke on the subject on March 5 at the Human Rights Committee of the Parliament of the Canton of Geneva.

Sir Geoffrey Nice QC wants the British government to confirm to the peers that sanctions, including travel bans and asset freezing, would apply to doctors who violate the law by engaging in forced organ harvesting. Lord Hunt’s question to the British government on March 2, reported by the BBC even before it was asked, built pressure for just such government action.

In addition to those mentioned above, according to Matas, a growing number of researchers have been active on the issue, including Jay Lavee, Susie Hughes, Grace Yin, Zhiyuan Wang and Huige Li.

Do your duty

The tribunal concludes with a call to governments and international bodies to “do their duty” and act against this atrocity. “Governments and international bodies must do their duty not only in regard to the possible charge of Genocide but also in regard to Crimes against Humanity, which the tribunal does not allow to be any less heinous.”

Government action must include economic and travel sanctions on China generally and those most responsible specifically, until the country stops forced organ harvesting against prisoners, including those of conscience like the Falun Gong.

With the evidence for such atrocities piling up, it will be increasingly difficult for companies, universities, and governments to continue turning a blind eye to the lack of ethics emanating from the CCP. Paying more attention, calling out China and naming names is a good thing, because we need to send the country and its enablers a message.

As the tribunal states, we can all pitch in and insist on this change to help someone in prison who is being dehumanized as just a future organ transplant. Demand reform now. Someone’s life is depending on it.

Anders Corr holds a Ph.D. in Government from Harvard University and has worked for U.S. military intelligence as a civilian, including on China and Central Asia.

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official editorial position of LiCAS.news.

© Copyright 2020 LiCAS.news

This article was published March 13, 2020.

ETAC Student Movement

ETAC Student Movement