Western democracies grapple with how to close down China’s atrocities in Xinjiang

Governments sanction Chinese officials for their treatment of Uyghurs, but there seems no plan for what to do next

The events of the past couple of weeks have brought to international focus a dark sector of ongoing Chinese policy that Beijing routinely dismisses as an internal affair and no one else’s business.

As images of huge prison-like complexes in Xinjiang province are picked up by one global news network after another — coupled with harrowing eyewitness accounts of systematic rape and torture of inmates — major global economies have finally decided to act.

The sheer scale of China’s ethnic cleansing of the Uyghur population and irradicating itself of their way of life cannot be underestimated. There are an estimated 13.5 million people living in this region rich in natural resources, such as oil and gas, gold and cotton.

Since the formation of communist China in 1949, Uyghurs are the piece that has not slotted neatly into the nation’s ‘Unified China’ puzzle and the authorities have tried numerous methods to jab that metaphorical piece into place.

Central government has over time offered ethnic Han Chinese all kinds of incentives to move to Xinjiang and intermarry with Uyghurs, but progress has been slow with the Han reluctant to settle in the region.

Meanwhile, Uyghurs have continued to resist Beijing’s influence, resistance which has occasionally turned bloody, resulting in more direct methods of control.

A vast sprawling system of camps, or what communist China euphemistically describes as re-education centers, now forms an ominous spider’s web across Xinjiang — “transformation through education” is the government’s mantra.

At least 3 million people, including 500,000 children, have been processed through this system where inmates are reportedly subject to brainwashing and torture. Female inmates have also reported rape at the hands of their guards.

Beijing has tried to fob these allegations off as isolated incidents but the list of harrowing tales of suffering just keeps growing.

Background photo: cotton field in Xinjiang, China (Photo by Captain Wang / shutterstock.com)

Meanwhile, researcher Adrian Zenz — whose research has sparked renewed global interest in the region — used open-source data published by the Chinese government to highlight widespread forced sterilization of Uyghur women.

Allegations have also more recently come to light of more than 80,000 Uyghurs have been forcibly removed from their homes in Xinjiang and relocated to work elsewhere in China, thus adding to the argument of ethnic cleansing.

Zenz’s revelations last year subsequently attracted the attention of British broadcaster, the BBC, which had until recently published a series of revealing documentaries on Xinjiang and Uyghurs.

With Beijing’s dirty laundry laid out for the world to see, the image was such that major global economies could no longer afford to turn a blind eye. Added to which, it has come to light that more than 80 multinationals — including household brands such as Burberry, Nike, Adidas and H&M — had been sourcing their cotton from companies using forced labor in Xinjiang, a public relations nightmare, regardless of the brands’ subsequent attempts to distance themselves.

New poster for

— 巴丢草 Badiucao (@badiucao) March 27, 2021

BOYCOTT any company using #XinjiangCotton

STOP #UyghurForcedLabour

SANCTION CHINA FOR #UyghurGenocide

FREE #Uyghurs FROM CCP'S #ConcentrationCamps pic.twitter.com/NN87A7e1CT

So, a number of countries — including the UK, Canada and the US — have sanctioned high ranking Chinese officials. Beijing’s annoyance at this perceived effrontery is such that it has responded in kind.

Today, Minister Garneau responded to #China’s sanctions against Canadian parliamentarians and democratic institutions. Canada will continue to work collaboratively with partners to address the dire #HumanRights situation in Xinjiang.

— Foreign Policy CAN (@CanadaFP) March 27, 2021

Read full text: https://t.co/LDEc35mtpx pic.twitter.com/MjFkDpBcp7

The Chinese government has also seen fit to expel the BBC, but its likely reasons for this include ongoing disputes with London over Hong Kong and UK regulators ripping up Chinese state media channel CGTN’s broadcasting license.

At the same time, Facebook has reported Chinese-based cyber attacks on Uyghurs living overseas.

About 500 Uyghurs in a few different countries were being targeted by the Chinese hackers. Looks like I’m one of them. @Facebook pic.twitter.com/H3TDROGFT3

— Ferkat Jawdat (@ferkat_jawdat) March 25, 2021

Background photo: chinese flags on barbed wired wall in Xinjiang (Photo by Jonathan Densford / shutterstock.com)

Sanctions at the highest level are largely symbolic and more a diplomat’s way of saying someone has crossed the line, but a US-Sino summit recently collapsed with leaders doing little but mudslinging over the Xinjiang issue, pointing to the possibility the US is not prepared to give up so easily.

However, the question of how to approach a looming humanitarian crisis such as this is not an easy one to answer. China insists its policies in Xinjiang are part of its Belt and Road initiative, and that ultimately the region will benefit.

An increasing number of nations disagree, witnessing more and more disturbing reports of ethnic cleansing and the denial of a people’s right to self-determination. Yet these nations are all economically intertwined with China in a way that makes withdrawal from partnerships a distinctly less than palatable prospect.

Chinese and US flags flutter outside the building of an American company in Beijing, Jan. 21. (Photo by Tingshu Wang/Reuters)

Chinese and US flags flutter outside the building of an American company in Beijing, Jan. 21. (Photo by Tingshu Wang/Reuters)

Liberal western society may be appalled by scenes coming out of Xinjiang, but they similarly rejoice in the array of cheap, quality Chinese-made goods in their stores. History has proven that consumers become remarkably short-sighted and will turn on their own governments first as prices rise or products are withdrawn from the market altogether — as the US recently found out to its cost.

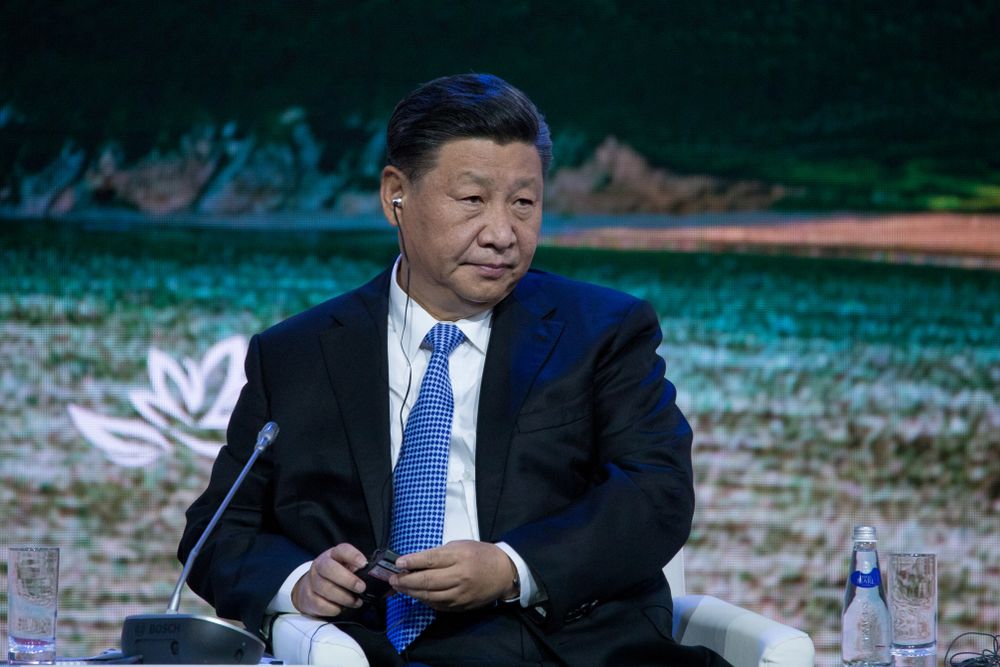

Chairman of the People's Republic of China Xi Jinping at a 2018 forum in Vladivostok. (Photo by Alexander Khitrov/shutterstock.com)

Chairman of the People's Republic of China Xi Jinping at a 2018 forum in Vladivostok. (Photo by Alexander Khitrov/shutterstock.com)

Background photo: Soldiers of People's Liberation Army march in formation past Tiananmen Square during the military parade marking the 70th founding anniversary of People's Republic of China, on its National Day Oct. 1, 2019. (Photo by Jason Lee/Reuters)

Meanwhile, with the Belt and Road initiative forming the backbone of Chinese foreign policy, it has astutely managed to exert influence over nations largely ignored by the West, through massive infrastructure deals.

Countries across Asia and Africa, once desperate for nation-building income and expertise, find themselves bound by terms that only favour China. Moreover, Muslim trading partners like Pakistan are similarly stifled by extradition treaties requiring them to hand over any Muslims China wants or face an economic savaging.

Turkey was once a go-to refuge for people fleeing Xinjiang and Ankara was vociferous in its condemnation of China. Now — frozen out by Europe and the US over a deteriorating democracy, and faced with an economy in freefall — President Recep Tayyip Erdogan is mysteriously silent about the issue when that huge, juicy Chinese economic carrot dangles before him.

Moreover, in tandem with communist China’s resolute stubbornness and aggression, President Xi Jinping will likely be playing the odds that the West — or even the UN — will not have much stomach for a fight, economically at least and definitely not militarily, unless outright provoked.

Arguably, the last time the UN stood up to China was in 1950 during the Korean War. Since then, China has invaded Tibet, which it still occupies, and Vietnam three times since the US left in 1975, plus sporadic armed conflicts with nuclear neighbour India.

Beijing also views the South China Sea as its backyard, regardless of current borders, and has threatened to invade Taiwan.

Meanwhile, the West stood back and watched as at least 15 million Chinese were slaughtered by their own government during the Great Leap Forward from 1958 to 1962, and a further 500,000-plus perished in the Cultural Revolution four years later, not to mention more recent events like the bloody Tiananmen Square massacre in 1989 and the crackdown on democracy in Hong Kong.

Beijing will also have noted UN or NATO backed debacles in Afghanistan, Iraq and Libya, coupled with the West’s impotence in handling Syria and Ukraine.

So, it would be reasonable to assume — given the twists in logic of authoritarian regimes — that senior figures in the Chinese hierarchy would be asking why the sudden interest in Xinjiang.

This is aside, of course, from China propping up some of the world’s most notorious dictatorships and despots, as we have seen in Myanmar and North Korea — and the West again doing very little to intervene.

Therefore, for China, this is a waiting game. Eventually, the West will get bored and move on to its next ‘project’, then it is back to business as usual.

For the West, despite the rhetoric of standing up to China, governments must privately be hoping the news cycle moves on swiftly to something else.

By Gareth Corsi

Published April 1, 2021

© Copyright MMXXI LiCAS.news